Bronwen Durocher leads us on an exploration of authors and their pets:

Whether he or she serves the author on the page or in their laps, animals (and the pet, in particular) have long been central to the comfort and inspiration of a vast array of famous writers. Gérard de Nerval wrote about the virtues of lobsters, Flannery O’ Connor let peacocks take over her gardens in Georgia, Carl Sandburg kept dairy goats in North Carolina, and Byron had a bear at Cambridge. One may be tempted to think of these pets as the whimsical byproduct of the fanciful and artistic temperament, but I think Flannery O’ Connor answered this critique best when she wrote

Once or twice I have been asked what the peacock is ‘good for’—a question which gets no answer from me because it deserves none.

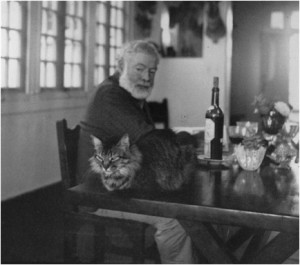

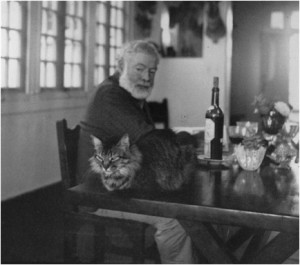

From what I’ve gleaned from living in New York, cats are the pet of choice for the be-spectacled, book-laden urban-dweller. The Archipelago Books staff boasts three cats between us, which is respectable, if unremarkable. Samuel Clemens, for one, is said to have furry felines numbering in the double digits, and Ernst Hemingway housed and fed an estimated 23 cats at his home in Key West. On the virtues of the cat, Hemingway once wrote,

A cat has absolute emotional honesty: human beings, for one reason or another, may hide their feelings, but a cat does not.

[Photo credit: brainpickings.org]

[Photo credit: brainpickings.org]

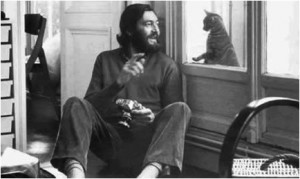

Archipelago authors share Hemingway’s sentiments. Jacques Poulin, author of Archipelago’s Mister Blue, Spring Tides and Translation is a Love Affair, often writes cats into his narratives. In Mister Blue, the protagonist’s cat becomes a metaphor for the elusive nature of language:

Words are independent, like cats, and they don’t do what you want them to do. You can love them, stroke them, say sweet things to them all you want – they still break off and go their own way.

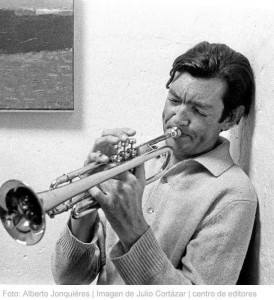

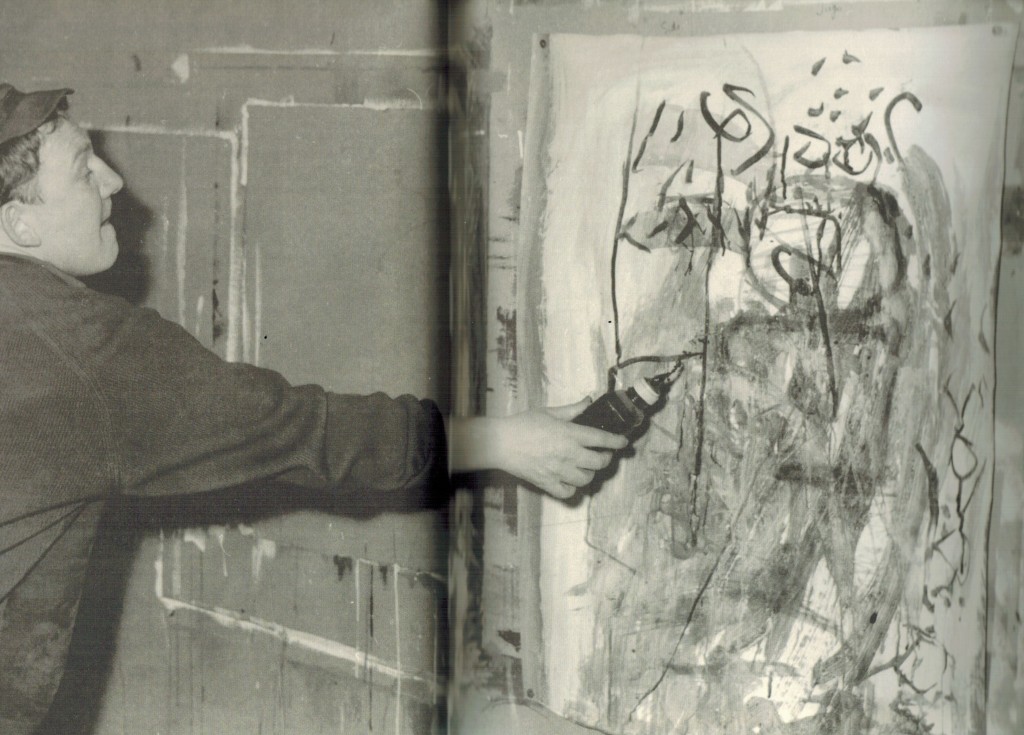

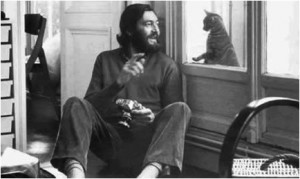

Julio Cortázar, author of Archipelago’s Autonauts of the Cosmoroute, The Diary of Andrés Fava, and From the Observatory, is photographed here with his furry feline, Theodor W. Adorno. [Image courtesy of: alexisravelo.wordpress.com]

Julio Cortázar, author of Archipelago’s Autonauts of the Cosmoroute, The Diary of Andrés Fava, and From the Observatory, is photographed here with his furry feline, Theodor W. Adorno. [Image courtesy of: alexisravelo.wordpress.com]

Like Jacques Poulin, Julio Cortázar was an unabashed cat lover. In Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, Cortázar wrote,

I sometimes longed for someone who, like me, had not adjusted perfectly with his age, and such a person was hard to find; but I soon discovered cats, in which I could imagine a condition like mine, and books, where I found it quite often.

Around the Day in Eighty Worlds is littered with references to animals, from a distracted writer who follows the travails of a fly, to a contemplation of the eradication of crocodiles in the Auvergne region of France, to the proliferation of the “everyday” jaguar. This is perhaps unsurprising considering the protagonist of Cortázar’s famous short story “Axolotl” obsesses over the tiny Mexican amphibian until he becomes one.

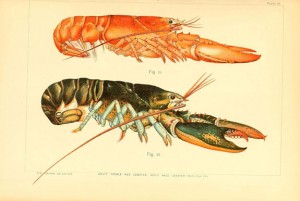

Cortazar’s affinity for strange animals is only outdone by the amusing and eccentric French author, Gérard de Nerval. According to his friend Guillaume Apollinaire, de Nerval could be seen taking his pet lobster for walks in the Palais-Royal gardens in Paris in the late nineteenth century. (This apocryphal tale is highly unlikely. Lobsters can’t survive more than 30 minutes or so out of water.) His response to his friend’s questioning serves as an apt ending to this post:

And what could be quite so ridiculous as making a dog, a cat, a gazelle, a lion or any other beast follow one about. I have affection for lobsters. They are tranquil, serious and they know the secrets of the sea.

For more on famous author’s pets, read Brain Pickings’ lovely article here. For photos of writers and their animals, see Flavorwire’s slideshow here and for an in-depth analysis of animals and pets in literature, read 50 Watts’ article here.

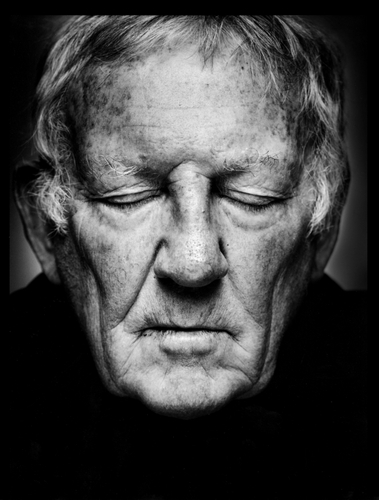

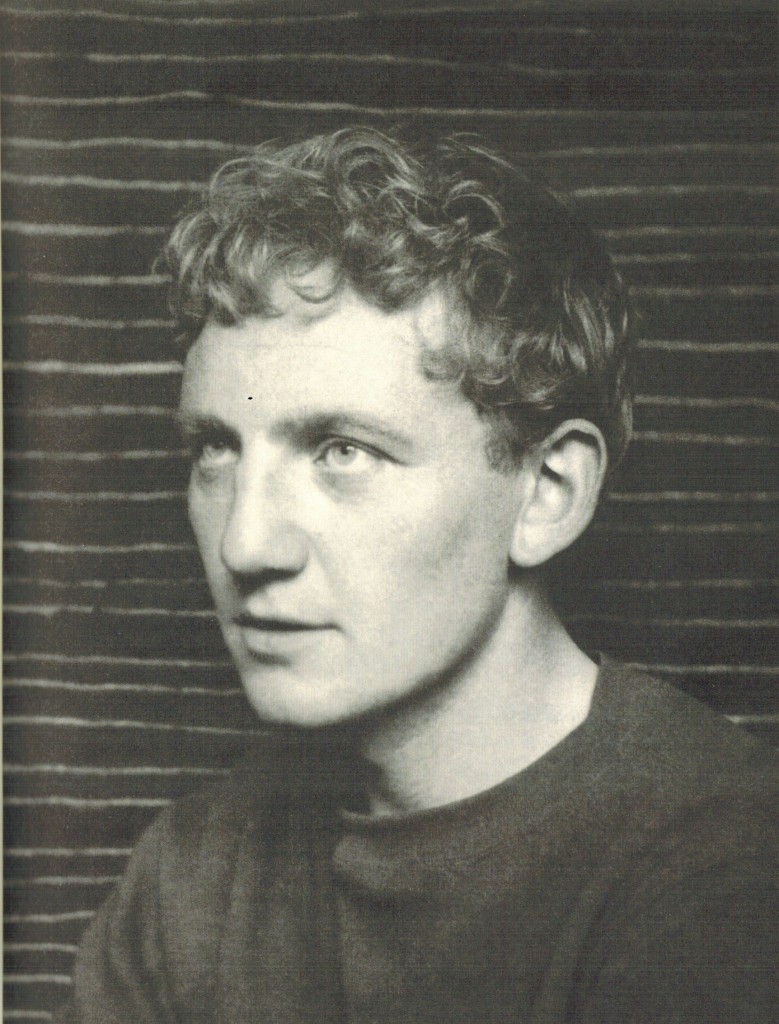

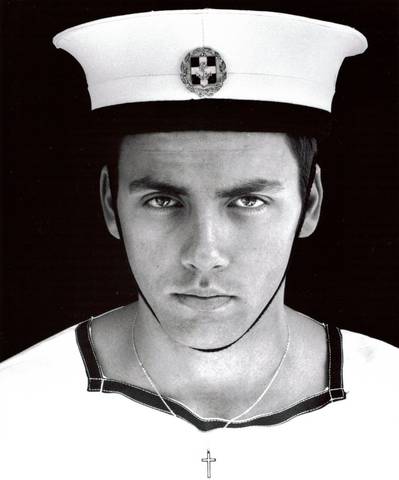

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]