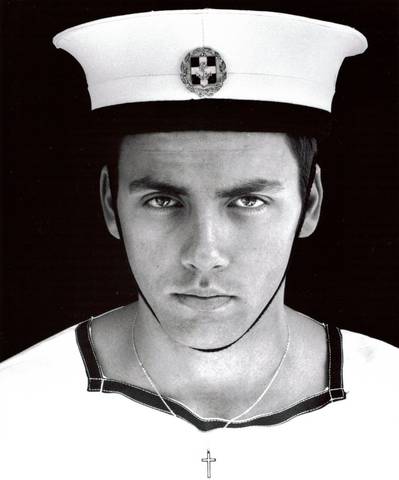

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

I just came across this article about comparing translations of Constantin Cavafy’s “The City”, and thought I would throw a few more ideas and translations of the last stanza into the mix.

First, a translation from our own Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard (C.P. Cavafy, Collected Poems. Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. Edited by George Savidis. Princeton University Press, 1992).

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you. You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods,

will turn gray in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

The directness, here, electrifies the voice of Cavafy. The tone feels cavernous and cold, which lets the idea of an inescapable reputation ring and echo throughout. They chose to include contractions. The poem seems to beg to be spoken, something which I tend to like, and the intimacy helps the drive till the end.

Next, Rae Delven’s 1948 translation lauded by, among others, W.H. Auden:

You will find no new lands, you will find no other seas.

The city will follow you. You will roam the same

streets. And you will age in the same neighborhoods;

and you will grow gray in these same houses.

Always you will arrive in this city. Do not hope for any other–

There is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you have destroyed your life here

in this little corner, you have ruined it in the entire world.

I love the inversion of “Always you will arrive in this city.” The emphasis of “always,” rather than feeling archaic, seems to hammer home the point. Interesting how the next line — “There is no ship for you, there is no road” is exactly the same as Keeley/Sherrard’s. “Destroyed” certainly adds a much different texture than “wasted.”

And, finally, Daniel Mendelsohn’s recent 2009 translation:

You’ll find no new places, you won’t find other shores.

The city will follow you. The streets in which you pace

will be the same, you’ll haunt the same familiar places,

and inside those same houses you’ll grow old.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t bother to hope

for a ship, a route, to take you somewhere else; they don’t exist.

Just as you’ve destroyed your life, here in this

small corner, so you’ve wasted it through all the world.

The most colloquial of the three, Mendelsohn’s translation hits the point in a different way, like the hurtful rant of a drunken uncle you admire. For some reason — maybe it’s the relentless commas instead of periods — this translation feels more disparaging. The speaker not only advises against hope, but says “Don’t bother to hope…” Things seem already to have been decided. A life is already “wasted…through all the world.”

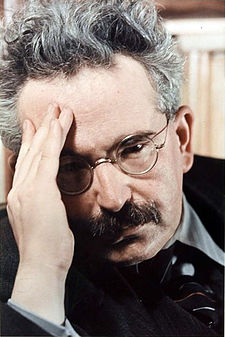

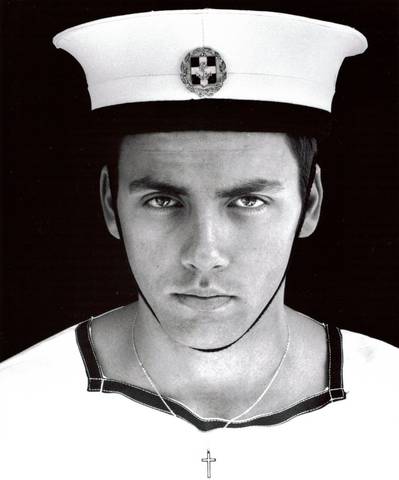

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]