Catalan translator Mary Ann Newman kicks off our GUEST POST series which features translators, thinkers, and enthusiasts in the field. Newman offers her invaluable insight into the underappreciated world of the translator:

The core challenge for translation is the question of professionalism. What, for translators, is almost always a vocation, is treated by the publishing industry as an avocation. The office of translator, and the act of translation, is gravely undervalued, and all the judgments that derive from this lack of esteem–compensation, reflection in reviews, presence in bookstores, etc.–suffer the effects.

I believe there is a blind spot in this regard. One of the great Catalan fiction writers, Quim Monzó, is also a great translator, with a true vocation. Twenty years ago he wrote what amounted to a manifesto renouncing translation. His reasoning was professional: publishers paid whatever the market rate was for paper, ink, machinery, wrote off checks of 200,000 pessetes for cover art that took at most a day, and in many cases, a matter of minutes, and yet balked at paying translators more than 100,000 pessetes for three to six months’ work. Monzó makes his living as a writer and a journalist: he was not willing to treat translation as anything less serious.

This challenge, this unacknowledged professionalism, contains its own opportunity. Translators must devote our own (precious, underpaid) time to reflecting on our work, both theoretically and empirically. The Translation Committee of PEN American Center has been grappling with these questions and will soon be publishing a toolkit to offer support and solutions, and a reviewers’ Hall of Fame to acknowledge excellence in translation criticism.

Strides have been made of late in bringing attention to translated literature–the Bridge Series, Chad Post’s Three Percent website, Susan Bernofsky’s Translationista blog, et al.–, and translations, even from lesser-known languages, are proliferating. Yet there is still a sense of swimming against the tide. Recently translators have been trying to establish a dialogue with publishers and reviewers–in sessions at the PEN World Voices Festival or the ALTA conference, for example–but both groups have seemed loath to cede much territory to translation. Some publishers are fearful that any mention of the translation, or space devoted to the translator’s name, is a disincentive to purchase. Reviewers, often constrained to 500- or 750-word reviews, are reluctant to expand the space they allot to mentioning the translator’s name and “able” or “seamless” (or “clumsy”) translation. Or, they are understandably fearful of making mistakes when they do not speak the original language or have knowledge of the context of the text.

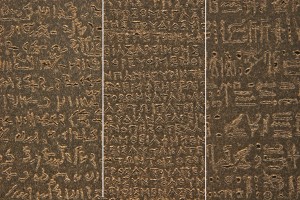

The standard attribute of a quality translation–its invisibility–is at least partially responsible for the situation. Translations are not invisible. They are palpable and three-dimensional: that book you hold in your hands (or on your kindle) was written by a translator, no matter who the author is. The translation is an indispensable stage in the history of the text. The translator is a witness, a privileged actor in the regeneration of the text. He or she has information no one else is privy to, and which every reader could potentially be interested in.

Hence it would be useful for translators to provide publishers and reviewers with interesting information regarding, let’s say, the history of the book–if it is a rediscovered classic, why did it fall out of favor, or why was it never translated?; or the challenges of the language–what words, phrases or concepts have no equivalent, and might affect the reception of the book?; or the cultural or literary context: what aspects of the book have appeared in criticism and reviews in the original language, to which reviewers do not have access?; what are the possible parallels in English or other familiar languages; what historical information will enrich references in the text?…

Translators are shape shifters: we perform and are transformed by every new book and author and character even as we transform the text. And we are accustomed to being the handmaidens (and manservants) of authors. We can also serve the publisher, reviewer, and, ultimately, the reading public, by bringing the translated text into the foreground. But we must also be warriors: denial or omission of the translation is, frankly, not only lazy but duplicitous. There is no reason for translations not to be hot properties or for their sale not to be good business. Translators can help make them cool or sexy. But there must be a sea change in the perception–no, the attitude–of the industry toward the translated work and toward the translator’s role.

We claim to live in a globalized world–translation is our medium. Surely it is time for translators, publishers and reviewers to sit down together and bang out a new set of rules.

Mary Ann Newman is the former Director of the Catalan Center at New York University, which was an affiliate of the Institut Ramon Llull. She is a translator, editor, and occasional writer on Catalan culture. In addition to Quim Monzó, she has translated Xavier Rubert de Ventós, Joan Maragall, and Narcis Comadira, among others.