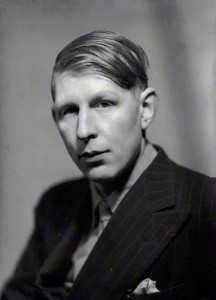

If you’re going to engage with English poetry, a mentor once told me, sooner or later, you’re going to have to deal with Pound. She was referring, of course, to his controversial–and often, downright bigoted–remarks both on the page and beyond. But frankly, few modern English poets have influenced as many writers as Pound. That his work continues to resonate with successive generations poses a particular challenge in the narrative history of American verse.

Pound recognized the need for international literature to enliven the language, incorporating untranslated text from other languages into his poetry and even translating whole works (see: Enrico Pea‘s Moscardino). Avoiding the mode of stiff, word-to-word translation, Pound followed his ear, sometimes creating a translation that was outrageously loose — but gorgeous.

And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly seas, and

We set up mast and sail on that swart ship,

Bore sheep aboard her, and our bodies also

Heavy with weeping, and winds from sternward

Bore us out onward with bellying canvas,

Circe’s this craft, the trim-coifed goddess.

My favorite example of his translation skills is in his “Canto I.” The majority of the poem is a loose translation of a brief episode from Homer’s Odyssey. Notice the trios of alliterative words and vowel-sounds at the beginnings of each line. Rather than follow Homer’s dactylic hexameter meter, which doesn’t work in the same way as it does for Ancient Greek and Latin, Pound chose to set the poem in a similar meter as Beowulf. Pound saw his task beyond translating the words: he translated the meter, from one language’s epic tradition to another.

For those in the know — or willing to Google the reference — Pound admits toward the end that he isn’t translating from the original Greek, but from a 1538 Latin edition translated by Andreas Divus. Pound’s resulting creation feels like a direct address to the Art of Translation, its wonders, its pitfalls, and its importance.

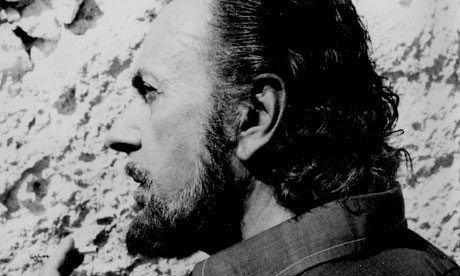

Check out all of Canto I on the Poetry Foundation website here, with a great recording of Forrest Gander giving his thoughts and reading the first section.