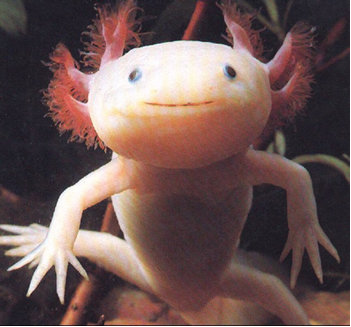

An axolotl: one of the creatures in Caspar Henderson’s The Book of Barely Imagined Beings

An axolotl: one of the creatures in Caspar Henderson’s The Book of Barely Imagined Beings

[image courtesy of http://southerncrossreview.org ]

Every so often, we’d like to share some of our book recommendations around the office. For the first installment, Florence fills us in on a few of her recent reads:

The Infatuations, Javier Marias

A murder mystery for lovers of Éric Rohmer. The plot is simple: a book editor at a publishing house becomes infatuated with a glamorous couple who she sees every morning at a café on her way to work. One day she sees in the newspaper a photograph of the husband, who has been brutally murdered, and becomes embroiled in a love triangle that involves his mourning widow and his eternal-bachelor best friend. These events veer close to pulp, but that’s the point: this is the ultimate highbrow/lowbrow novel. Marias breaks down moral questions to their basest level, a move that gives him the space for reflections on time’s passing, the fickle nature of memory, guilt, and death, thereby elevating an archetypal tale to the level of Greek tragedy.

The widow reflecting on death:

…. there is also an impulse toward death: ‘I want to be where he is, and the only place where we could coincide is the past, in that place of not being but of having been. He is past, whereas I am still present. If I were also past, at least I would be the same as him in that respect, which would be something, and I would be in no position to miss him or remember him. I would be on the same level as him or in the same dimension, in the same time, and we would not be left alone in this precarious world in which everything familiar is being taken away from us. Nothing more can be taken away from us if we are not here. Nothing more can die on us if we are already dead.’

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary, Caspar Henderson

A wonderful compendium of animals that are all the stranger for being real. Henderson allows himself to roam from natural history to moral philosophy to personal reflection, employing the essay’s digression-friendly form with a dexterity reminiscent of Montaigne, Samuel Johnson, W. G. Sebald, and Borges, to whom the title nods.

We meet the axolotl, a baby-faced salamander whose ability to regenerate limbs has aided in stem cell research; and tardigrades, a stubby, eight-legged polyextremophile which has survived in outer space for ten days. We also get to know more familiar animals better, including the octopus, whose blood runs with copper, not iron, and the dolphin, whose feats of libido made me blush (did you know a dolphin orgy is called a “wuzzle”? Beats gang bang).

But what makes this book worth reading is that it is not merely a catalogue of fun facts. Henderson’s body of knowledge ranges from evolutionary biology to archaic manuscripts, anthropology, and modern literature, and his sense of wonderment at natural history not only extends to these realms, but also beautifully gets at what it means to be human. What are our brains for if not to aid our greedy eyes? By this measure, the fox handily beats the hedgehog.

Also see the author’s awesome blog, a series of notes and comments on the chapters in the book: hyperlinks for those who’d rather call them marginalia.

Postwar, Tony Judt

I became determined to read this back in 2010 after Tony Judt’s devastating passing. Three years later, I have finally completed this task.

Despite the tome’s literal and metaphorical weightiness, its 800-plus pages do not sit heavily. Judt’s Renaissance Man-cultural touchstones and acerbic humor punctuate grim statistics and otherwise numbing political personalities: we are reminded of Mitterand’s backhanded compliment to Margaret Thatcher of “the eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe”, and Judt’s takedown of the individualism of the ‘60s and 70s, a philosophy that he sees as placing the one above the many at the expense of a greater social good, is punctuated by his dissing of its cinematic parallel: Rivette’s “Celine and Julie Go Boating” (which I, personally, love. I guess a millenial would?)

Every chapter is enlightening and elegantly written. Postwar begins with an account of the refugee crisis following the fall of the Third Reich: the 8 million displaced persons and “unrepatriable” individuals who, whether due to civil war or Soviet occupation, refused to or could not return home. Judt is especially good on the decline of the Soviet bloc—its monopolies, fudged ledgers, and above all, its doomed inflexibility, its inability to dispatch regionalized versions of Communism, as exemplified by the Tito-Stalin split. I was also impressed by his chapters on Belgian, Catalan, and Balkan regionalism which, to grossly oversimplify, show separatist movements emerging where unequal wealth accrues.

If the book has a thesis, it’s that a “Europe” exists at all, a claim that may seem hollow today, as EU-Turkey talks are delayed over protests in Taksim Square. “What binds Europeans together . . . is what it has become conventional to call – in disjunctive but revealing contrast with ‘the American way of life’ – the ‘European model of society’.” At its core is the Europeans’ “deliberate choice to work less, earn less – and live better lives.” In return for high taxes, they receive “free or nearly free medical services, early retirement and a prodigious range of social and public services.” And not far behind this agreement lurks WWII: its utter devastation of the land and economy, painstakingly detailed in this book, meant European governments were forced to start from scratch. It is not surprising that out of such horrors was borne a social contract guaranteeing its citizenry’s basic needs. As a young American who expects to find social security’s coffers empty when the time comes, I can admit to some envy of this grand bargain. And thanks to this truly magisterial, erudite, and eye-opening work, I have a better sense from whence it came.