It’s always a surprise when presidents or kings or prime ministers or otherwise powerful heads of state reveal a poetic side. Sometimes it’s laughable, but other times — considering they were probably busy dealing with things like the defeat of the Spanish Armada or mending the wartorn homeland — the poetry’s not so bad. Here are two of my favorite examples from English:

The Suicide’s Soliloquy

by Abraham LincolnHere, where the lonely hooting owl

Sends forth his midnight moans,

Fierce wolves shall o’er my carcase growl,

Or buzzards pick my bones.

No fellow-man shall learn my fate,

Or where my ashes lie;

Unless by beasts drawn round their bait,

Or by the ravens’ cry.

Yes! I’ve resolved the deed to do,

And this the place to do it:

This heart I’ll rush a dagger through,

Though I in hell should rue it!

Hell! What is hell to one like me

Who pleasures never know;

By friends consigned to misery,

By hope deserted too?

To ease me of this power to think,

That through my bosom raves,

I’ll headlong leap from hell’s high brink,

And wallow in its waves.

Though devils yell, and burning chains

May waken long regret;

Their frightful screams, and piercing pains,

Will help me to forget.

Yes! I’m prepared, through endless night,

To take that fiery berth!

Think not with tales of hell to fright

Me, who am damn’d on earth!

Sweet steel! come forth from our your sheath,

And glist’ning, speak your powers;

Rip up the organs of my breath,

And draw my blood in showers!

I strike! It quivers in that heart

Which drives me to this end;

I draw and kiss the bloody dart,

My last—my only friend!

Pretty dramatic. But since he’s Abraham Lincoln, we’ll let it slide. Another, which, taken with the title, really strikes me:

Written with a Diamond on her Window at Woodstock

by Queen Elizabeth IMuch suspected by me,

Nothing proved can be,

Quoth Elizabeth prisoner.

That titular image — the avian Queen scratching a royal jewel across the window — sets a particular lonely and ridiculous mood before we even reach the poem.

The closest we’ve come to presidential poetry in this century are, shockingly, from George W. Bush. His bizarre self-portrait paintings leaked onto the internet some time ago, and, as arts blogger Greg Allen so astutely observed:

The amazing thing is not just that they literally show Bush’s own perspective—but that Bush is using the process of painting to show his own perspective. It’s a level of self-reflection, even self-awareness, that seems completely at odds with his approach to governing.

They may not send ripples through the contemporary art world, but they do seem to speak to the emotional life of a public political figure, a rarity. And in this case, to eerie effect.

Well done, rulers.

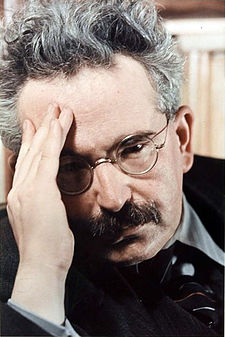

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

[ from Stahis Orphanos’s MY CAVAFY which pairs Cavafy’s poems with contemporary portraits ]

[ image courtesy of

[ image courtesy of

[scene from

[scene from