A few facts about translation through the ages, from our intern Alison Silver:

The word “translation”

- Derives from the Latin for “the carrying from one place to another.”

Classical:

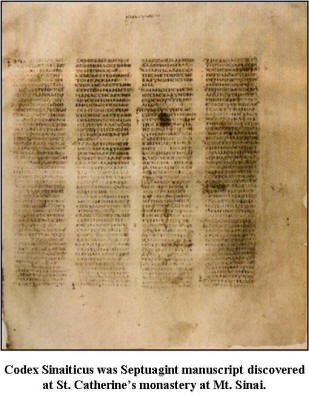

- 300-200 B.C.E. First major translation in Classical World was Septuagint (pre-Christian translation of Hebrew Bible/Jewish Scriptures into Koine Greek). Septuagint means seventy in Latin and is the name of the Bible because of the believed seventy translators who completed it.

[ image courtesy of truthnet.org ]

[ image courtesy of truthnet.org ]

- Cicero said of his translation of Demosthenes that the translator must reproduce the original work in adherence to the conventions of Latin usage.

Early English

- The first high quality English translations were from the great English poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, called “grant translateur” by contemporary French poet Eustache Deschamps.

- Medieval literature centered on Chaucer’s tradition of free adaptation.

- The first major English translation was the Wyclif (Wycliffe) Bible c. 1382, and English prose translation began a century later with Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, a free adaptation of Arthurian romances.

- 1412 Archbishop Arundel wrote to the pope that Wycliffe was a “wretched and pestilent fellow of damnable memory, … the very herald and child of anti-Christ, who crowned his wickedness by translating the Scriptures into the mother tongue.”

- Shortly after, a provincial council at Oxford issued a decree stating that “no one shall in future translate on his own authority any text of holy scriptures into the English tongue—nor shall any man read this kind of book, booklet or treatise, now recently composed in the time of the said John Wycliffe or later, or any that shall be composed in future, in whole or part, publicly or secretly, under penalty of the greater excommunication.” This decree lasted until 1453 with the fall of Constantinople when scholars brought Greek texts to the West.

Renaissance

- In Italy, Petrarch had collected Greek manuscripts to translate, and Marsilio Ficino undertook a Latin translation of Plato’s works. Along with Desiderius Erasmus’ Latin translation of the New Testament, these works introduced a new approach to translation that emphasized exactness, particularly in preserving the exact wording of religions and philosophical figures like Jesus, Plato, and Aristotle.

- More freedom of poetic interpretation arose from The Pléiade (a group of Renaissance poets in France) and Tudor poets’ translations of works by Horace, Ovid, and Petrarch, after a growth in the middle class and the development of printing technology created the desire to translate original writing into contemporary language to entertain the public.

- 1611 translation of the King James Bible, resulting from collaboration of almost 50 translators

- 1612 Thomas Shelton completes the first part of an expanded version of Don Quixote, followed by Cervantes’ publishing of the second part.

Restoration and 18th and 19th Centuries

- Translation was becoming an industry, in which writers were paid little but nonetheless made a living on translation projects, including collaborations with their contemporaries.

- 1683-1686 John Dryden’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives

- 1697 John Dryden’s translation of the Aeneid

- 1715-1720 Alexander Pope’s translations of the Iliad

- 1725-1726 Alexander Pope’s translation of the Odyssey

- Standards for translation heightened in the 19th century regarding style and accuracy. Victorian efforts, like Thomas Carlyle’s translations of Goethe’s writings, Sir Richard Francis Burton’s Arabian Nights (1885-1888), and William Morris’ translation of Beowolf (1895) strived for literal translation in order to preserve the classic quality of the original text, even at the expense of modern-day comprehensibility.

- 1813 Friedrich Schleiermacher wrote a treatise in German entitled “On the Different Methods of Translating,” in which he advocated that “Either the translator leaves the writer in peace as much as possible and moves the reader toward him; or he leaves the reader in peace as much as possible and moves the writer toward him.”

20th Century

Notable translations of the era include:

- 1871 Benjamin Jowett’s translation of Plato alters convention by reproducing the work in plain, understandable terms and not the archaic language of the original.

- 1922-1931 C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past

- 1925-1933 Arthur Waley’s translation of Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji

[scene from

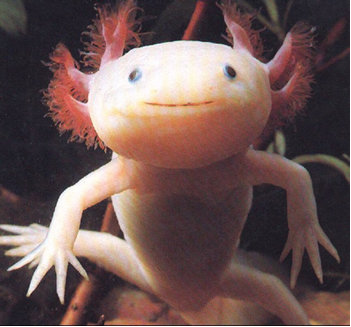

[scene from  An axolotl: one of the creatures in Caspar Henderson’s The Book of Barely Imagined Beings

An axolotl: one of the creatures in Caspar Henderson’s The Book of Barely Imagined Beings