Category: Reading Group Guides

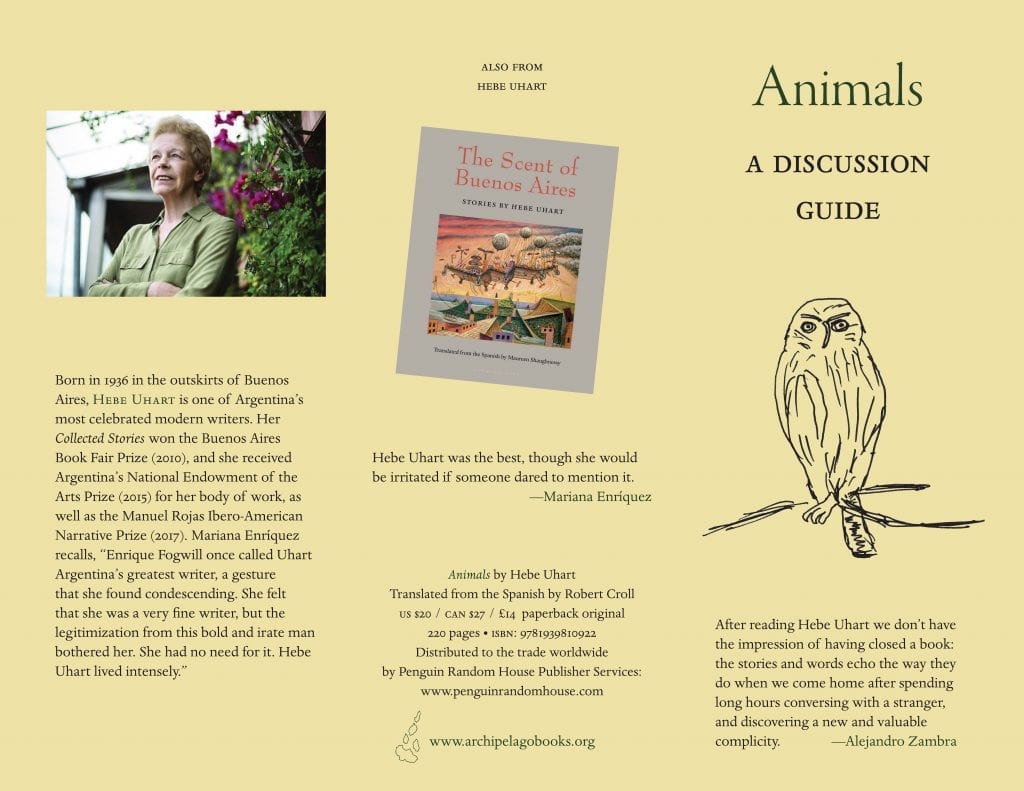

Reading Group Guide for Animals Copy

Reading Group Guide for Animals

Reading Group Guide for If You Kept a Record of Sins

Reading Group Guide for Igifu Copy

Reading Group Guide for The Distance

Reading Group Guide for Difficult Light

Reading Group Guide for Igifu

Reading Guide for Our Lady of the Nile

Our Lady of the Nile

By Scholastique Mukasonga

Translated from the French by Melanie Mauthner

Click here for a PDF of this Reading Guide

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- The lycée of Our Lady of the Nile dominates the book, both as a setting and as a symbol for both the past and future of Rwanda and Africa as a whole. What things do you notice in the first few pages of the novel that describe the construction of the lycée, its location, its symbolic force? By the end of the novel, how do we view the lycée? Is it a force for good, for bad, or something more complex?

- The unveiling of the statue of Our Lady of the Nile and its christening provides a potent symbol for the overarching goal of the lycée, to create a new African ruling class rooted and educated in the traditional European (white) values, in other words black educated (or “civilized”) Christians. As we move through the novel, to what extent is that project successful? Where are moments in the novel where its failure is explicit? And what do we make later in the novel about the fact that the former Virgin Mary had been painted black and so became Tutsi? See “The Virgin’s Nose.”

- The concept of the white man’s burden (i.e. that white’s have an obligation to ‘civilize’ non-whites through education and religion, but also to preserve and protect elements of the indigenous cultures under the assumption that the indigenous culture wouldn’t be able to do so themselves) is omnipresent in the novel. What examples do you see? For example, one stark instance is the episode of the gorillas, presumably referencing the famous primatologist Jane Goodall as well as Monsieur Fontenaille. Furthermore, how does Mukasonga present these instances, and in what ways does she criticize them?

- References to witchcraft, witchdoctors, curses, spells, and poisons abound in the novel. These ‘pagan’ aspects of the native Rwandan culture exist side by side with the Christian presence, and while they would seem to be opposed, rather seem to intermingle into something distinct. Where do you see this sort of fusion happening? Or what are some instances where the seemingly primitive practices and beliefs of witchcraft come into contact with very modern and contemporary events or figures? As an example, look at the episode describing the theft of the saber of the King of Belgium.

- How does language function in the novel, especially as it relates to colonialism and issues of power? The lycée is a French only zone where Swahili or other native languages are not permitted. To push further, remember that Mukasonga wrote the novel in French, the language of the education that eventually allowed her to leave Rwanda and move to France, escaping the devastation of the Rwandan genocide that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands, including the vast majority of Mukasonga’s family. What does it matter that she has written the novel in the language that both saved her and yet was the language of the ruling class that did so much harm to her native country?

- We are told incessantly that the purpose of the lycée is the advancement of the Rwandan women. To what extent are the lives of the women/girls we meet in the novel improved or advanced? At the very beginning of the novel, we read, “The young ladies of Our Lady of the Nile know just how much they are worth.” (8). What are they worth? What are the options for these women? Simply political bargaining tokens for men wishing to advance their own interests, even if this brings the women personal security and even luxury? Is this feminism? And if so, of what sort? Pay particular attention to the case of Frida, described in the section “Up the Virgin’s Sleeve.”

- At the end of the section “Up the Virgin’s Sleeve” Frida’s death is hushed up, not mentioned, and essentially silenced from the collective memory of the lycée, ranging from the teachers to the students. Mukasonga writes, “For there was now a shameful secret lying coiled deep within the lycée, and deep within each of the girls, too; remorse in search of a culprit; a sin that could never be purged since it would never be owned” (132). We can generalize Frida’s death to the millions of deaths that eventually occurred during the genocide, or even deaths that occurred as a result of colonialism more generally. It’s clear that part of the grieving process, part of what allows Mukasonga to move forward in her life, is this ‘owning’ of the sins, both collective and personal. The way one owns the sin is to tell it, to write it, to make the secret visible. What other instances of secrets, forgetting, or erasing do we see in the novel? And to complicate matters further, what do we make of the witchdoctor’s comment, “The whites wrote the secrets down”? (146).

- There is much white fantasizing about the black body, both physically and understood in a more general cultural sense, ranging from the mythic to the sexual, even the perverse. Consider the cases of Father Herménégilde, Monsieur de Fontenaille, and Father Pintard. What unifies these separate cases, and at one points do they differ? How does the white gaze play into these cases as well? Consider this quote: “’here, we’re [as Tutsis] inyenzi, cockroaches, snakes, rodents; to whites, we’re the heroes of their legends’” (165).

- The conflict between the Hutu and the Tutsis permeates the novel, through quotidian interactions all the way up to more explicit discussions and terminating in violence. Although the horrors of the Rwandan genocide of 1994 was still many years away from the time in which the novel occurs, violence against Tutsis was becoming more and more commonplace during the time of the novel. What foreshadowing do we find? And what do we make of the explicit alignment of the Tutsis with the Jews (119, 164) by Father Herménégilde and Father Pintard, especially considering the novel takes place in a post-Holocaust world? The most poignant example is the final two episodes of the novel.

- What do we make of the final episode of the novel, where the prejudice boils over into nightmarish violence? The occult appears once more as a major force, providing safety to Virginia. Does the novel end on a hopeful note? What do the gorillas come to represent in the final scene?

Reading Group Guide for The First Wife

The First Wife

by Paulina Chiziane

Translated from the Portuguese by David Brookshaw

Click here to download a PDF of this reading guide

Discussion Questions

- The novel opens with a Zambézian proverb: “A woman is earth. If you don’t sow her, or water her, she will produce nothing.” How does correlating the feminine with the natural impact the perception of women in society? Does this empower women or feed into patriarchal constructions of femininity? How?

- How do the different women in the story—Rami, Lu, Ju, Saly, and Mauá—cope with their disadvantaged social positions? How do their mothers and aunts cope?

- How do the institutions of polygamy and monogamy each define femininity? Do the definitions overlap?

- Many of the northern women who are proponents of polygamy consider southern women prudish and traditional to a fault. In what ways is monogamy an outdated notion?

- In the novel, the North is portrayed as a matriarchal culture where polygamy helps women maintain their status and ensures wellbeing. Does the institution of polygamy help or hurt the women in the story?

- At times it seems that Rami is breaking the chains of southern Mozambican patriarchy with radical and disobedient notions. Yet other times, she clings onto the status quo and is shocked when the northern women attempt to act beyond their restraints. Is Rami truly attempting to transcend cultural hegemony, or is she simply seeking revenge?

- Chiziane has said that “western medicine is almost mechanical, it treats the heart, the foot, the eye, while traditional medicine goes beyond.” How does traditional medicine function in the novel? Does it help Rami find peace in her marriage?

- In what ways do Rami’s problems change or develop and in what ways do they stay the same?

- How do Rami’s intentions morph as her relationship with Tony degenerates? Does she remain committed because of love, or something else?

- At what point does Rami fall out of love with Tony and why?

- Rami creates a working relationship with Tony’s other women and even helps them develop their entrepreneurial skills, yet she still refers to them as her rivals. Does Rami ever overcome this internalized misogyny, and how can we begin to interpret the complex relationships Rami holds with these other women?

- Does the novel’s resolution result from Rami and the other women taking initiative in their lives and marriage, or is it more a product of exterior cultural forces and Tony’s negligent behavior?

Additional Questions

- Could Rami have moved on from her failing marriage without the child that resulted from her kutchingering? Would Tony let her leave otherwise?

- Chiziane criticizes Mozambique’s overall patriarchal societal structure yet holds on to other cultural precedents, such as the importance of traditional healers. How does Chiziane navigate the complex web that is tradition? What role do healers, potions, and spells play in the novel and how are they portrayed within the overarching patriarchal hegemony?

- Rami’s story is a very culturally specific one, but in what ways is The First Wife actually an ode to women everywhere?