(Sun setting over the Bosphorus. Silhouettes of Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque and the Süleymaniye Mosque. Image courtesy of Seha Islam through Wikimedia Commons.)

(Sun setting over the Bosphorus. Silhouettes of Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque and the Süleymaniye Mosque. Image courtesy of Seha Islam through Wikimedia Commons.)

In another installment of our international travel posts, Archipelago’s Bronwen Durocher celebrates novelist Ahmed Hamdi Tanpinar‘s A Mind at Peace by taking us on a tour of Istanbul.

Istanbul in the summertime is an enchanting city. Local art, grand bazaars, intricate mosques with spindly minarets reaching toward the heavens, and sweeping views of the glistening Sea of Maramara make Istanbul an attractive destination for history lovers and pleasure seekers alike. Founded in 660 B.C., Istanbul (originally Byzantium and then Constantinople) boasts over sixteen centuries of cultural and intellectual history as the capital and political center of first the Roman, then Byzantine, then Latin and finally Ottoman empires, respectively. Walking along the modern streets and promenades, it’s tempting to imagine peeling away the modern, westernized layer to get a peek at the centuries of grand human history and empire that lie beneath. Nuzzled in the crook of the Sea of Marmara, Istanbul straddles Europe to the West and Asia to the East, and has long served as a trading post between these two spheres. Yet it would be wrong to say that Istanbul is somehow transitory or in-between. Istanbul has absorbed and withstood change from Roman to Christian to Islam and back again, and the wavering top-down secularism of the twentieth century has produced a unique blend of culture and unease that can’t be called distinctly European or Eastern or religious or secular because Istanbul is both East and West, both religious and secular.

To get a better sense of this paradox, and what it was like to live amongst the crumbling ruins of the once great Ottoman empire in the 1930s, I recommend Archipelago’s A Mind at Peace. Called “[t]he greatest novel ever written about Istanbul” by Orhan Pamuk (who recently told The New Republic that the future of the novel lies with the soaring middle classes of places like Turkey, India, and China), the book is, at its heart, a love story best absorbed while sipping strong Turkish tea and munching on fried eggplant with yogurt sauce or almonds with honey. The novel does a wonderful job of describing the very personal sense of loss that the narrator feels in conjunction with the modernization of the 1930s while immersing the reader in the literature and music of a fading empire.

Of course, novelists can only give a sense of the malaise and discontent in a city that’s ostensibly rejected it’s Ottoman past wholesale. (Turkey’s first prime minister, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk reportedly forced citizens to throw their traditional Turkish fezzes into the Bosphorus river.) Today, the city is experiencing the growing pains that accompany a bid to join the EU alongside an increasingly Islamic political agenda. The protests in late May of this year began as an environmentalist critique of the urban development plan for Taksim Gezi Park in Istanbul and morphed into a wide-reaching display of national unrest. Many protesters are unhappy with the rapidly changing political landscape and their increasingly authoritarian prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. On the current climate, secularist and novelist Orhan Pamuk says he is opposed to Erdoğan’s policies, yet he cedes, “Secularism that has to be defended by the army comes at a cost.” To make sense of this shift, he explains in the New Republic that sometimes it is the job of a writer to elucidate certain peculiarities or nuances of a people and a culture.

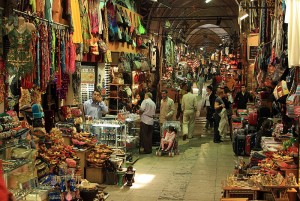

The current political climate is not one that should deter potential travelers. The clashes of May and early June have ceased, and the U.S. lifted its travel alert in early July. This is welcome news for readers of a Mind at Peace who wish to wander the streets of the Beyoğlu district, smell spices hanging in tiny shops in the Grand Bazaar, or feel the tug to Mecca from their hotel balconies when they hear the Blue Mosque issue a call to prayer. Below are just a few choice recommendations for visitors to this thriving, pulsating city.

(Vendors sell a wide array of goods including backgammon sets, clothes, shoes, and other trinkets at the Grand Bazaar. There are over 5,000 shops in the complex. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

(Vendors sell a wide array of goods including backgammon sets, clothes, shoes, and other trinkets at the Grand Bazaar. There are over 5,000 shops in the complex. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

The Grand Bazaar: In 1461, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror ordered the construction of a grand trading post next to his palace so he could keep an eye on the treasures collected from his massive, expanding Ottoman empire. Though Mehmed the Conqueror’s name invokes the rape and pillaging associated with conquest, the sultan encouraged deported people and prisoners of war to settle in Constantinople, and was especially keen to attract Greek and Genovese traders (even though it was the Greeks he had conquered to take over the city). Mehmed’s program of re-populating Constantinople included the construction of a new palace, a bazaar, and many mosques. In 1461, the bazaar was a place to trade goods pouring in from new settlers and conquerors hailing from as far as the Republic of Venice and Italy in the West and Asia Minor or Anatolia in the East. Here they traded cotton, silk, gold, silver, weapons, shawls, carpets, and other precious possessions from across the empire. Over 500 years later, precious ceramics, tiles, swords and jewelry are still being bought and sold in the same space. Located in the Fatih district, the Grand Bazaar stretches from the mosque of Beyazit to the West and the Mosque of Nuruosmaniye to the East. The bazaar can be reached by tram from from Sultanahmet and Sirkeci.

(Lights hang from above at the Sultan Ahmed Mosque or The Blue Mosque. Image courtesy Sean Caffrey http://www.lonelyplanet.com/turkey/istanbul/images/sultan-ahmed-mosque-istanbul$26044-6)

(Lights hang from above at the Sultan Ahmed Mosque or The Blue Mosque. Image courtesy Sean Caffrey http://www.lonelyplanet.com/turkey/istanbul/images/sultan-ahmed-mosque-istanbul$26044-6)

Sultan Ahmed Mosque (The Blue Mosque): Built in the early seventeenth century during the rule of the Sultan Ahmed, the Blue Mosque is considered the last great mosque of the classical period of Turkish architecture. Heavily influenced by the Byzantine Greeks, and modified to fit the needs of an increasingly powerful Ottoman capital, the mosque’s nine domes, six minarets, ten marble columns and over 200 stained glass windows were designed to expose over 20,000 hand-painted tiles to natural light. Intricate tile designs in the sun-drenched domes coupled with thick Turkish carpets on the floors and a finely carved marble mihab (a decorative niche carved into the wall to indicate the direction of Mecca), lend the massive interior a sense of splendor and majesty felt by the mosque’s many visitors. The Blue Mosque, named for the blue tiles that line its interior, can be reached by taking the tram or metro to the Sultanahmet station in the Fatih district of Istanbul.

Bookstores: After you’ve visited the Blue Mosque and the Grand Bazaar, I would recommend taking the tram to Istiklal Caddesi in the pedestrian-friendly Beyoğlu district. Here you can browse a few lovely English-language bookshops conveniently huddled together in the neighborhood where foreign dignitaries built their embassies and homes in the nineteenth century. Deemed the most academic of the English-language bookstores in Beyoğlu, Caglayan Kitabevi carries English-language titles in a variety of disciplines including art, architecture, history, religion, psychology, and law. Just steps from Caglayan Kitabevi, Pandora Bookstore houses English-language titles on the third floor. Its English-speaking staff caters to Anglophones and ex-pats who browse their impressive contemporary fiction collection as well as their fantastic selection of Turkish poetry and art books in English. The stylish Robinson Crusoe bookshop is a short walk from Pandora and is known for carrying wonderful English translations of classic and contemporary Turkish literature. They also carry a wide variety of world literature titles, including Diary of Andrés Farva by Julio Cortázar, Yann Andréa Steiner by Marguerite Duras, and Travel Pictures by Heinrich Heine. And yes, they also carry Ahmed Hamdi Tanpinar’s love letter to a lost Istanbul, A Mind at Peace.

This defiant and somewhat melancholy quote from Ahmed Hamdi Tanpinar’s A Mind at Peace illustrates the idiosyncrasies associated with Turkish identity and provides welcome backdrop for any reading about Turkey you might do while visiting Istanbul:

“The things we read don’t lead us anywhere. When we read what’s written about Turks, we realize we’re wandering on the peripheries of life. A Westerner only satisfies us when he happens to remind us that we’re citizens of the world. In short, most of us read as if embarking on a voyage, as if escaping our own identities. Herein rests the problem. Meanwhile, we’re in this process of creating a new social expression particular to us.”

I hope the Istanbul you visit reflects this this “new social expression” Tanpinar imagined for his particular and extraordinary city.

Happy travels!