Review in BOOKFORUM Feb/Mar 2005, page 6

Thomas D’Adamo on Bacacay

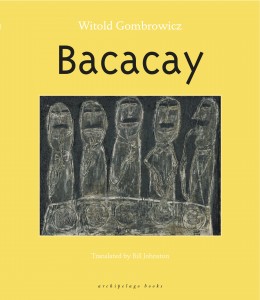

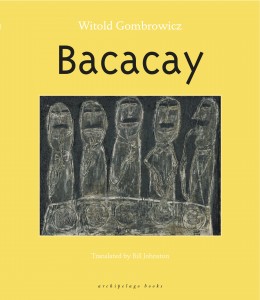

Bacacay by Witold Gombrowicz, translated from Polish by Bill Johnston

New York: Archipelago. 275 pages. $26

Somewhere in dada heaven, Witold Gombrowicz is having a good laugh over the Polish Ministry of Culture’s having declared 2004, the centenary of his birth, the Year of Gombrowicz. The irony of that honor being bestowed upon one of twentieth-century literature’s most ardent (and wittiest) foes of culture with a capital c—especially his native, Polish one—was surely not lost on his fans, who can well imagine how much mileage the author would have gotten out of that dog and pony show.

That Gombrowicz’s fiction eludes categorization is something of a commonplace in lit-crit circles. Nowhere is that slipperiness more apparent than in Bacacay, a collection of twelve short pieces now available for the first time in English (thanks to Bill Johnston’s crisply idiomatic translation), thirty-five years after the author’s death. Even the book’s title reflects its author’s caginess: The name of the Buenos Aires street on which he lived, Gombrowicz chose Bacacay, he explained in a letter to the book’s Italian publisher, “for the same reason that a person names his dogs—to distinguish them from others.” But just as you know a person by the company he keeps, you can begin to draw a bead on Bacacay by locating it among the works of other artists with whom Gombrowicz would have felt right at home. A short list of these might include Bruno Schulz, Eugéne Ionesco, the Marx Brothers, Terry Gilliam, Joseph Heller, Donald Barthelme, and George Saunders. Obvious differences aside, all of the above share a genius for toppling cherished cultural hobbyhorses and bidding us to revel in the ensuing anarchy—and, of course, the exceptional skill required to make what they do look easy.

A further clue to Bacacay can be found in Gombrowicz’s preface to his later novel Pornografia, in which he writes:

Man, tortured by him mask, fabricates secretly, for him own usage, a sort of “subculture”: a world made out of the refuse of a higher world of culture, a domain of trash, immature myth, inadmissible passions…a secondary domain of compensation. That is where a certain shameful poetry is born, a certain compromising beauty.

Written in the ’30s, the first ten stories of Bacacay are, to my mind, the purest expression of Gombrowicz’s lifelong commitment to charting that domain and giving exuberant voice to that compromising beauty. Reading these unforgettable tales of body parts at war with one another (“Philidor’s Child Within”), vegetarian aristocrats high on the taste of human flesh (Dinner at Countess Pavohoke’s”), crusty old seamen who prance around the deck in peacock feathers (“The Events on the Banbury”—imagine a cross between Ionesco’s Bald Soprano and a nautical version of Monty Python’s “Lumberjack Song”), and a tennis match that erupts into a melee among upper-crust prigs mounted piggyback on their ladies (Philiber’s Child Within”), one gets a good sense of what Susan Sontag meant when she said that great literature is secreted. No carefully plotted clockworks these, each story obeys an internal logic as unique as its creator’s fingerprints.

Rebellion against the infantilization wrought by the tyranny of cultural forms and norms is a persistent theme throughout Gombrowicz’s work. In most cases, rebellion expresses itself in fetishes or bizarre ritual behaviors, as in “On the Kitchen Steps,” which follows the life of an elegant aristocrat who spends his nights bashfully pursuing only the dowdiest cleaning ladies, from whom he expects nothing more than boisterous ridicule. Better yet is the arresting “Virginity,” the story of a cloistered maiden who is plunged into an existential crisis after being hit by a rock thrown by a derelict who appears atop her garden wall one day. Stunned and a bit turned on by the assault, the young woman begins, for the first time in her life, to question her much-vaunted purity, eventually coming to see in it a pernicious ignorance both of herself and of the world. The story culminates in one of the most unnervingly funny scenes in late-modernist fiction, as the virgin entreats her horrified fiancé to join her in gnawing on a rotting bone picked out of a garbage heap: “Come on, the bone’s waiting for us, let’s go to that bone! We’ll gnaw it together—do you want to?—together! Me with you, you with me! See, I already have it in my mouth! And now you! Now you!”

Reminiscent of the protagonist in Alberto Moravia’s existentialist classic, The Conformist, Stefan, the young man at the center of the poignant “Memoirs of Stefan Czarniecki,” longs for conventionality the way a prisoner craves freedom. In his desperation to “wash away the stain of [his] origins” (his mother is Jewish), Stefan becomes an ultranationalist and war hero, only to have the rug pulled out from under him by the crazed laughter of a comrade who is horribly ripped apart by an artillery shell. Haunted by the sound of that laughter, Stefan returns from the war an embittered nihilist. Wherever he sees “some mysterious emotion, whether it is virtue or family, faith or fatherland, I always have to commit some villainy. This is mystery, which for my part I impose upon the great enigma of being.”

The final two stories in Bacacay, “The Rat” and “The Banquet,” (the latter written during the author’s self-imposed exile in Argentina) have neither the vitality nor the subtlety of the others. These parables—one, the story of a bigger-than-life brigand terrorized by a rat; the other about a king who solicits tips from his courtiers—read more like expositions of signature themes than joyously subversive explorations. The result is that the author for whom immaturity was a reasoned philosophical and aesthetic stance, in attempting to “do Gombrowicz,” comes off sounding just plain immature. Given the significance of these early works, however, that criticism seems trivial at best.

Thomas D’Adamo is a writer living in New York.

*This review was originally published in

BOOKFORUM, issue Feb/Mar 2005, page 6