Translation is the medium through which American readers gain greater access to the world. By providing us with as direct a connection as possible to the individual voice of the author, translation provides a window into the heart of a culture.

Author: archipelago

He says a lot, for a Norwegian

“If I had known what was coming, I would never have been able to do what I did, because it’s been like hell, really hell,” he said. “But I’m still very glad that I did it.”

Knausgaard, in a fascinating article by Larry Rohter for the New York Times, describes his life after the six-part publication of My Struggle, and its connection with Hitler’s infamousMein Kampf.

Read it here.

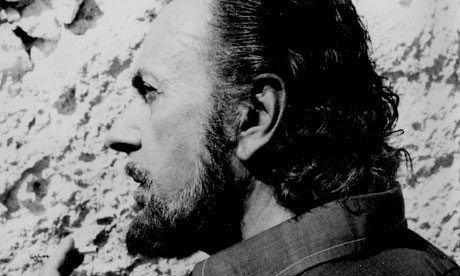

My hero: Yannis Ritsos by David Harsent

“The poet’s extraordinary productivity was achieved in the face of personal tragedy, persistent ill healthy and systematic persecution”

David Harsent, forThe GuardianUK, writes a moving piece on the legacy of Yannis Ritsos.

Read it here.

Kitty recommends "My Struggle"

Our intern’s cat catching up on Archipelago new release MY STRUGGLE!

Book of My Mother is book of the month!

Thank you to Green Apple Books for making Albert Cohen’s BOOK OF MY MOTHER their blog’s book of the month! http://thegreenapplecore.blogspot.com/2012/06/your-mother-should-know.html

"My Struggle" on display at Third Place Books

Third Place Books’ Reading the World display featuring Karl Ove Knausgaard’s MY STRUGGLE!

Review of Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer from Tony Miksanek in Journal of the American Medical Association

Rats—the small rodent kind and the large human kind—figure prominently in Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer. Hordes of rats infest this novel, and they are nearly impossible to exterminate. Georg Letham, the narrator of this sprawling story, is a 40-year-old European physician with self-destructive tendencies and a deep affection for money. Although Letham prides himself on his ability to inspire trust, he is not trustworthy. By the end of the book, the twisted physician rediscovers his humanity and uncovers the epidemiology of yellow fever.

Letham’s life is full of contradictions. He admits to being lucky but gripes about his misfortune. He spends his nights either working in the laboratory or gambling. He is both a criminal and a scientist. Although his main interest is experimental bacteriology, Letham begins a private practice concentrating on surgery and gynecology. In hindsight, his exodus from research is a bad choice. He is not a people person: “Illness interested me, the ill did not.”

Letham’s tragic flaw is carelessness. While investigating scarlet fever, he transmits streptococcal sepsis to 2 surgical patients. He is unfaithful to his older and wealthy wife, and he later murders her by administering a deadly toxin. He is sloppy and leaves evidence—an empty vial and syringe—behind. He goes to trial, and his punishment for poisoning his wife is a life sentence of hard labor in a penal colony.

Meanwhile, yellow fever is wreaking havoc on the tropical island where Letham is sent for imprisonment. The mortality rate from the infection is as high as 55%, and the etiology and transmission of the disease are as yet unknown. Typhus, leprosy, tuberculosis, and malaria also vex the inhabitants of the island. In all, an appropriate environment for a physician-murderer who happens to have an interest in microbiology research. Letham is quickly put to work in a makeshift hospital set up in a former convent. A group of 5 persons including Letham, a fellow convict, 2 physician-scientists, and the prison chaplain (a priest with an “Amen” tattoo) set out to identify the cause of yellow fever and how to stop its spread. They intend to infect themselves with the disease. The men are willing to sacrifice their own lives (along with the lives of others) to find an answer: “Physicians have experimented on human beings from time to time for as long as medical science has existed. It has not been exactly the rule, but by no means the exception, either, that physicians have ventured to experiment on themselves.”

Their self-experimentation is “successful.” Letham contracts yellow fever and endures its terrible symptoms but survives. Others are not so fortunate: 2 men die as a result of the experiment. The scientists prove that the Stegomyia mosquito is the vector of transmission. The governor of the prison island authorizes a program to eradicate the mosquitoes, with the aim of eliminating yellow fever. Letham’s influential father pulls some strings to obtain clemency for his son, and in light of Letham’s sacrifice and service, the murderer receives a pardon. Although he must remain in exile on the island, he is allowed to ply his trade as a physician.

Medical ethics is a hot topic in this novel. Yet the story addresses several important issues beyond the proper behavior of physicians and the moral code of conduct for medical researchers: justice, punishment, altruism, the fear of illness, the joy of recovery, the ecstasy of being alive, and the absolute worth of a single human life. Slowly and painfully, the physician-murderer comes to understand the duty of a physician—which is first and foremost to provide solace for the patient.

The author, Ernst Weiss, has medical credentials. He served as a ship’s physician and as a military physician. He was a friend of Franz Kafka, a survivor of tuberculosis and attempted suicide. First published in German in 1931, the book is now available in an English translation. Although the first half of this marathon-like novel is often tough sledding, it finishes strong. Part medical detective story and part criminal confession, Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer is a long and risky read. From a literary standpoint, readers can expect a sizeable reward for their effort.

Review of Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer from Tahla Burki in The Lancet Infectious Diseases

His life story itself is the stuff of novels. Born in 1882 to a well-to-do Jewish family in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire—now the Czech Republic—Ernst Weiss spent his youth in some of central Europe’s most agreeable cities: Prague, Brno, Litomerice, and Berlin. He studied medicine in Vienna and later became a surgeon. 1912 saw Weiss take up a berth on a ship bound for India and Japan. When he returned to Europe, the storm clouds were gathering. He served with distinction as a military physician in the Great War: they awarded him the Golden Cross for bravery. Afterwards, he settled in Prague, but he didn’t want to be a doctor anymore.

Before the war, Weiss had struck up a friendship with Franz Kafka, who said of him “what an extraordinary writer he is”. Not everyone agreed: 23 publishers turned down Weiss’ first novel The Galley (1913). He moved to Berlin—where he wrote Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer—but by 1934 things were looking dangerous for central Europe’s Jews, and Weiss fled to Paris. There he lived an impoverished existence, eased by handouts from literary supporters such as Thomas Mann. In 1938, Weiss wrote The Eyewitness, his last novel, which contained a thinly veiled portrait of Hitler; a final act of defiance perhaps, for as the Nazis invaded Paris, Weiss drank poison. He died the following evening.

Astonishingly, it has taken until now for Georg Letham: Physician and Murderer to be translated into English. Joel Rotenberg has done a fine job of rendering Weiss’ snappily sardonic prose. It is presented in a handsome binding by Archipelago books. The eponymous antihero is a bacteriologist who murders his wife. He does so partly for money, partly because she repulses him, but mainly, you can’t help but feel, because he wants to spill blood. Letham is condemned to spend the rest of his life on a far distant penal colony, known only as C, where yellow fever is rampant.

It’s a distinctive and vivid work. Weiss has a remarkable facility for conjuring up chilling scenes of desolation and decay. There’s an eerie account of a doomed expedition to the North Pole that brings to mind Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. Here, the sailors are forced to give over their vessel to the insatiable horde of rats that have overrun the ship. “The ship does not understand the rodents in its belly. They merrily go on living. They are not looking for any pole. They are not interested in meteorology, not in dialects, not in Eskimo folktales, not in Christianity. Food to be taken is all that exists for them. If a weaker, good-tasting creature is alive and they can catch it, then they kill it”.

The descriptions of the yellow fever patients are a uniquely piquant mixture of cold medical terminology and visceral human suffering: “the conjunctivae were yellow, shot through with distended scarlet venules. He gave off the foul carrion-like stench that is characteristic of the disease. The tongue and oral mucosa were unspeakably raw, as though the top dermal layers had been removed with a grater, taken down to the bare meat”.

The author questions whether scientific detachment be brought to bear outside the laboratory. “I will hold up a mirror to myself. With a steady hand. With the exacting eye of a scientist” Letham explains in the book’s foreword. In reality, of course, this is a man in thrall to his passions, though he despises himself for it. This novel, it should be noted, was first published in 1931 in a Germany not yet immersed in the terrible collective mania of the Nazi era, against which reason was no match.

There’s more than a hint of Dostoevsky to the book: murderous, itchily neurotic characters, scenes of animal maltreatment and human degradation; indeed, the passages concerning the prisoners’ voyage to C are more brutal and hopeless than anything in Memoirs from the House of the Dead. And like Crime and Punishment, Georg Lethamreads in places like a thriller. But there’s none of the Russian’s religiosity: Letham looks to science for his salvation.

Freud’s influence also looms large: there are dream sequences and lengthy passages concerning formative incidents from the protagonist’s childhood. It adds up to a heady journey into the recesses of a tortured soul. But it’s the imagery that stays with you—a remarkable, haunting work. An extraordinary writer indeed.

Review of Eline Vere from Ben Moser in Harper's

[A] masterpiece. . . . The Hague’s greatest writer, turn-of-the-century Louis Couperus . . . captured the city in a famous novel, Eline Vere. . . . For its roomy, chatty descriptions of life among the moneyed classes, it is a Buddenbrooks avant la lettre; for its restless heroine, trapped by social obligations, it’s a Dutch Madame Bovary. . . in Ina Rilke’s smart new translation, it anticipates the questions that would become so important for women in the decades to come: no longer content in a purely domestic world, what were they to do with themselves?

Review of My Kind of Girl from Graziano Kratli in World Literature Today

With Buddhadeva Bose’s My Kind of Girl, Archipelago Books adds a prominent Indian Bengali author to its unique catalog of “classic and contemporary world literature,” which already includes translations from twenty-five other languages. Arunava Sinha’s agile version of this short novel, originally published in india in 2008, makes it accessible to a wider audience, both in its native country and abroad. The classically simple structure, consisting of a framing narratie punctuated by four flashbacks, is highlighted by cinematically sharp and sparing prose, visually poignant and tersely apt to convey the moral of the tale. Four middle-aged men–a contractor, a government official, a medical doctor, and a writer–are forced to spend a winter night together in the waiting room of a railway station, when an accident along the line blocks all train traffic until the next morning. While the four strangers are trying to figure out the best way to adapt to the circumstances, a young couple opens the door, stands on the threshold for a few moments, and then leaves. Clearly newlyweds, they are lost in their love for each other and oblivious of everything else. Their sudden appearance and retreat prompts the four men to comment on this blissful yet short-lived condition, “the most amazing part of this amazing illusion”–in the writer’s words–that is life itself. As the discussion takes a more confessional turn, the four travelers engage in teling their own stories of youthful love, illusion, and delusion. Predictably enough, each one of them concerns a woman, and the teller’s particular relation to her–or more precisely, the relevance and significance that such a relationship acquires in retrospective. Each of these relationships, in fact, represents a turning point in the narrator’s life (although we hear the man’s version only), often disguised as a failure, a defeat, or a loss.

Although encouraged by one another, the four men quickly become their own audience, while the waiting room, first described as a “comfortless island,” morphs into an underground cave, an otherworld where the men are taken by their own recounting, and where they seem to remain in a trance fo reminiscence and regret until, released from this spell, they reemerge to the surface of their ordinary life. Caught in a sort of cathartic process, they strive to decipher “the invisible writing of the past,” and what comes back to haunt and illuminate each one of them is not the memory of a long-lost love, but the way in which such an event changed their lives forever. The question is not what did or did not happen, but what could have happened, and why it happened this and not another–any other–way. It is a classical question, and one that nurtures anxiety and obsession, the twin vultures of middle-aged man.

By the time the fourth and final story ends, it is dawn and the station is stirred back to life by the news of an approaching train. The four men, walking out of their trance, leave the room and board the train as perfect strangers. Only the writer remembers the fateful young couple and, suddenly recognizing them huddled together on the busy platform, tries to retain a glimpse of this illusion as the train rolls out of the station. More significantly, perhaps, by the time the reader emerges from the cave of confession and deception, the writer has become the Writer, and his auctorial voice is what eventually guides us through the bustle of the platform and out of the story. And in this subtle transformation lies perhaps the simplest truth of this finely tuned little novel in whcih Bose, writing at a critical moment in the history of his country, clarifies and claims the indispensable role of art and iterature in society.