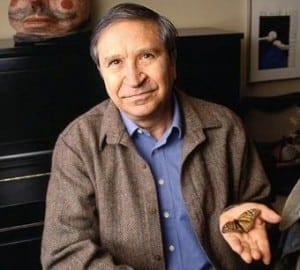

Krishna Baldev Vaid, the celebrated author of novels such as The Broken Mirror and Steps in Darkness, as well as numerous short stories, plays, diaries, works of literary criticism, and translations, died February 6, 2020. Throughout his life, Vaid wrote and taught at a variety of universities in both India and the United States. His novels and stories have been translated into many languages, Vaid himself having translated some of his own works, such as Steps in Darkness, into English. His prose was known for its experimental and distinctive narrative style. As Vaid said, his stories were not “mere stories” but created “an alternative reality … a universe of words and sounds and suggestions.”

Please read more about Vaid’s life and legacy here and in LitHub’s remembrance of Krishna Baldev Vaid, at this link.