Siberian-born author Rytkheu chronicles a Canadian sailor’s life among the Chukchi people of northeastern Siberia in a lyrical, instructional novel that reads like an adventure story wrapped around an ethnography. When ice traps John MacLennan’s ship in the Bering Strait in 1910, not far from a Chukchi settlement, the youthful, nave sailor, trying to widen a small fissure in the ice with dynamite, blows up his hands. His captain hires several Chukchi men to take him by dogsled to a Russian doctor—a long, arduous journey—and vows that the ship will wait for his safe return. But when gangrene sets in, John’s hands must be amputated by a medicine woman, and when strong winds break the ice shelf mooring the Belinda , the ship sails without him. The rest of the novel details John’s integration into the Chukchi world: adapting to his handicap, adopting Chukchi ways and finding friendship—and love—among his hosts. Even John’s role in the tragic, accidental death of his best friend, Toko, only pulls him deeper into the community’s folds. Rytkheu’s clear, compassionate prose (“Winter days resemble one another like twins”) ably evokes a foreign, fragile world.

Author: archipelago

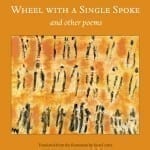

Wheel With a Single Spoke and Other Poems wins The Best Translated Book Award

Sean Cotter’s translation of Nichita Stanescu’s Wheel With a Single Spoke and Other Poems has won this year’s Best Translated Book Award! Click through for the full announcement.

3:AM Magazine interviews Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translators Reflections: Barbara Bogoczek on Różewicz’s Mother Departs

Mother Departs is an extremely personal autobiographical work by one of the greatest writers of our time, set against the epic conflicts of the 20th century. It combines many genres – poetry, jokes, intimate diaries written through tears, ethnographic snapshots of peasant life, and a dreamlike stream of consciousness – and it speaks in several different voices. I mean that literally: Tadeusz Różewicz brought together writings from close members of his family, including his mother and brothers. It flashes between the 1900s and the 1990s, back and forth, with one tragic moment in the Second World War at its heart.

To say that it was a challenge to translate it would be an understatement.

Click here for more.

"Neither Savage nor Noble:" a review of A Dream in Polar Fog from Neal Pollack in American Book Review

Yuri Rytkheu’s A Dream in Polar Fog is a reminder of a time when novels had adventure and mystery, before the ubiquity of video made everything on Earth seem familiar, yet also abstract and distant. Its themes are grand, elemental, and simple, comprehensible in the junior high school manner of discussing literature (Man v. Nature, Man v. Himself, and so on), but also tricky and subtle. This is the work of a writer in full command of the novelistic form. It recalls, in both substance and style, the best work of Jack London and Herman Melville, and it is a novel in the grandest sense of the world.

Unlike so many contemporary fiction writers, this author isn’t looking to impress us with his cleverness or with narrative trickery. He’s trying to reclaim the story of a people before it disappears forever, and his efforts give A Dream in Polar Fog an extraordinary urgency. Rytkheu is a descendent of the Chukchi people, an Arctic aboriginal tribe whose land happened to fall under control of the Russian Czar in the 1800s. His narrative begins at the dawn of the twentieth century, as modernity begins to make its creeping assault on the “authentic” Chukchi way of life. Rytkheu depicts that assault sympathetically while not descending unto the reductionist pits of political correctness. As he tells the story, the Chukchi are not savage, but neither are they particularly noble. Their simple life on the shores of an icy sea may have a kind of cleansing purity, but it’s also a hellish battle with the elements that seems, at times, inhuman.

Modernity arrives in the form of John MacLennan, the story’s protagonist, a Canadian sailor wounded in a gruesome accident and stranded by his mates to live in an alien Arctic wasteland. He serves as our narrative proxy. As he heals from his terrible injuries, our perspective on the culture unfolds along with his. He begins in abject terror, in a scene as terrifying as any in a contemporary horror movie, while a native shaman amputates his hands to stop the “black blood” of frostbite from stopping his heart; he truly believes that the Chukchi are going to eat him. Gradually, they nurse him back to health, and he becomes one of them, to the point where he marries a naÔve woman and fathers her children.

Yet this is no Dances with Wolves. The natives aren’t depicted as a pure alternative to the encroachments of the white men. Some of them are selfish, greedy, and superstitious. Others are prideful to a fault. While some of the native customs and myths Rytkheu describes are quite beautiful, some seem needlessly cruel. Similarly, the white men are depicted in various ways: some of the sailors the Chukchi encounter are honorable, while others seek to rob them of their food supply. Explorers arrive and offer aid, while greedy traders seek to accelerate the culture’s destruction for personal gain. Looming in the background are the Alaskan gold rush and, later, the Russian Revolution. In modern times, no people escape the torrents of history.

MacLennan, whose perspective occupies nearly the entire narrative, is himself a mess of contradictions. On the one hand, the book depicts his journey toward consciousness, both of himself and of nature’s greater plan. He learns to become self-reliant even without his hands, and quickly tries to stop imposing his own cultural values on the people who saved his life. But he’s also maddeningly self-righteous and self-sacrificing, working against his best interests even when his adopted tribe begs him otherwise.

Beyond the book’s grand themes and conflicts, which are many, Rytkheu depicts, simply but in great detail, the customs, traditions, and circumstances of a people whose lives are utterly unlike our own. There are walrus hunts, shamanic ceremonies, and long sled-drives across the tundra. By book’s end, you know what seal meat tastes like and how to bring a duck down from the sky without the use of a gun. There is a heartbreaking and harrowing famine chapter. The agony and chill feel palpable, and Rytheu makes a point quite strongly and surprisingly: modern people don’t have to suffer like this. They have heating sources and food in tins. Some traditions should endure, while others should fade into the past. Yesterday is different than tomorrow, cultures merge and transform, and the earth is a mutual entity. Those occasional departures from sentimentality give this novel a maturity that most books about “native” people seem to lack.

The Arctic landscape overwhelms all else in the book. It can’t be separated from the people who occupy it:

“Quietly, the ocean breathed. Water splashed by a thick faultline in the blue ice. Toko looked over to the eastern side of the sky, to where a distant cape pointed a long black finger at the vastness of the seascape. The sky above the crags was clear, nothing to indicate a change of weather. But you had to be careful in springtime. The wind could suddenly change, and the crevasse-covered ice could break into ice floes from a light breeze and carry the hunters out into the open sea.”

Rarely has humanity’s relationship to nature been so beautifully and vividly depicted. A Dream in Polar Fog is both elegant and exciting and also serves as a living anthropology of a gone world. It accomplishes everything a novel should.

Neal Pollack is the author of three books of satire, including The Neal Pollack Anthology of American Literature (McSweeney’s) and the rock-n-roll novel Never Mind the Pollacks (HarperCollins). He also edited the anthology Chicago Noir (Akashic). His memoir, Daddy Was a Sinner, will be published by Pantheon in the fall of 2006.

"Found in translation: Institute introduces globe's writers to U.S.:" a review of A Dream in Polar Fog from Eric Leake in The Las Vegas Sun

Novelist Yuri Rytkheu said his first surprise after leaving his village of hide-covered tents in Siberia was seeing fruit for the first time.

He said that the wonder he experienced then was akin to how he felt about his work finally being translated to English, and being invited to speak to an audience at UNLV about it on Thursday.

“In Sin City we actually found people who would come to hear this book being read about the corner of Siberia,” Rytkheu, 75, said through translation.

“This is really quite impressive.”

Rytkheu is the debut writer in the International Institute of Modern Letters Rainmaker Translation series. He spoke to an audience of about 50 people at the university.

Rytkheu’s novel A Dream in Polar Fog was published this month by Archipelago Books under the Rainmaker Translation seal.

Institute Associate Director Amber Withycombe said the publication is a significant event for the institute.

“We’ve been planning this series for a very long time. I guess, in a sense, the baby’s been born,” she said.

The institute was founded in 2000 by literary philanthropist and Mandalay Resort Group President and Chief Financial Officer Glenn Schaeffer. It funds international literary projects and has one of its locations at UNLV. The other is at a university in New Zealand.

Withycombe described the institute’s mission as both saving oppressed writers and making international writing accessible.

“It’s important to us to make American readers aware of these writings,” she said. “In an increasingly globalized world it seems like a very direct way to understand another culture. It’s unmediated, in a way.”

Douglas Unger directs grants and acquisitions at the institute and is director of the UNLV creative writing program. He said the institute’s mission is a response to the decreasing number of translated works published in America.

The institute cites a recent study by the National Endowment for the Arts that found less than 2 percent of the books published in the United States were translations.

“Intelligent readers and literary people were shocked by the study,” Unger said.

The institute, through the help of grants, funds the translation and marketing of selected works. The books are published by one of four partner firms.

Unger said it is important that American readers not be isolated from international writings.

“It shows us a completely different world and it makes us think about the values of other people,” he said. “When we consider their values it makes us take a look again at our own.”

The publication of the first Rainmaker Translation book, he said, also shows that Las Vegas is coming of age in a cultural sense.

“It’s helping the city assert a new kind of cultural identity, which is really great,” Unger said.

“It’s helping all us concerned thinkers and readers and people who care about the arts.”

He said the translation series fits the city well too, as it is an international destination and the nation’s first City of Asylum for oppressed writers, which the institute also supports.

The institute plans to eventually publish eight books a year under the Rainmaker Translation seal. Rytkheu’s is the first and will be followed next month by a collection of essays from Chinese writer Bei Dao.

Rytkheu spoke Thursday of his work and his native Chukotka region of Siberia.

The son of a reindeer herder, he has written more than 30 books in Russian, and many of them have been translated into Scandanavian languages, German and Japanese.

He said it is an honor to be the debut author in the series and that his novel is well suited to be his first in English for a Western audience.

A Dream in Polar Fog is a novel that is part historical, part adventure and part ethnographic study. It is the story of a Canadian sailor who becomes stranded with the Chukchi people.

Rytkheu’s novel is of a meeting of cultures and he spoke to the value of reading foreign works.

“It’s as important as people speaking to one another. If people didn’t talk to people who weren’t like them then the whole point of human interaction would come to nothing,” he said.

Rytkheu wore a digital camera around his neck and mentioned his cross-cultural impression of Las Vegas.

“It’s an incredible place unlike anywhere else,” he said.

Rytkheu, with his translator Ilona Chavasse, was to speak again at 2 p.m. today at the Borders bookstore on Stephanie Street at Sunset Road.

"Cold Comforts:" a review of A Dream in Polar Fog from John Ziebell Las Vegas City Life

Siberian author Yuri Rytkheu champions a native people in A Dream in Polar Fog

While he may be unfamiliar to American audiences, acclaimed Siberian author Yuri Rytkheu’s works are both popular bestsellers and award-winners throughout Europe and in Japan. Rytkheu was born in Uelen, a village in the Chukotka region of Siberia, and has extensive real-life experience from a region many people could not point to on a globe; he has hunted whales, sailed the Bering Sea and worked on scientific expeditions to the Arctic. In the course of a writing career that has spanned 10 novels and five decades, Rytkheu long ago emerged as the foremost literary voice for the area’s native Chukchi people, his works introducing a spectrum of readers to the history and mythology of one of the last truly desolate spaces on the map. He holds on to this distinction with A Dream in Polar Fog, which recently saw its first English-language publication. The translation was launched by Archipelago Books, a nonprofit publishing house committed to introducing a geographically and culturally diverse collection of writers who have been “overlooked” by commercial and university presses.

When asked if he viewed writing about the Chukchi as choice or obligation, Rytkheu once said, “Only God and inspiration dictate my topics.” He is, however, an uncompromising champion of the north’s native peoples, especially since the collapse of the Soviet Republic, when social programs for indigenous Siberians were cut back or totally abolished. He also has a long association with environmental issues and is a vocal critic of the devastation visited upon the Chukotka environment by Russia’s particularly ruthless methods of extracting natural resources. In the final analysis, Rytkheu’s fellow Chukchi appear to be in a position similar to that of any culture whose existence is based on a connection to the land – trapped somewhere between progress and tradition, facing choices that all bear some unforeseeable element of cost and loss.

A Dream in Polar Fog is, at its most basic level, an adventure story set along the rugged Arctic coastline. But Rytkheu’s novel is also about the impact of cultural collision, in this case between a band of traditional Chukchi and a white outsider. After a tragic shipboard accident, a seriously injured Canadian sailor named John MacLennan is left in the care of the Chukchi in the hopes that they can transport him to a Russian hospital. The native Siberians see their visitor as a strange but not unfathomable human being; MacLennan, on the other hand, views his saviors – and they do indeed save his life – as cannibal heathen, alien to what he considers normal behavior in every way. MacLennan will of course achieve a more generous point of view, in time, but it’s not an easy process for anyone involved.

Rytkheu’s novels have long been considered “ethnographic” for the amount of detail they provide about traditional Chukchi life, and while the author maintains that recreating that atmosphere was his greatest challenge, it’s something he handles quite deftly. Rytkheu’s narrative allows readers to develop insights into traditional Chukchi culture far more quickly than MacLennan, though the archetypal sailor’s prejudices and misprisions never seem too heavy-handedly didactic. The story is rich with seductive physical detail, and as we find ourselves immersed in arctic culture, an almost surreal relationship with land and weather, shamanistic rituals and even primitive surgical procedures begin to seem like part of everyday life rather than exotic episodes. The graceful translation by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse retains the native words for terms that probably don’t have very exact analogs in any other language – just what would you call a kind of yurt for sled dogs?

"Slip inside a dream wrapped in 'Polar Fog':" a review of A Dream in Polar Fog from Arthur Salm in The Union Tribune

Some ineffable quality — call it art — in Yuri Rytkheu’s prose and Ilona Yazhbin Charvasse’s translation transforms his hypnotic, shimmering new novel into exactly what its title promises: “A Dream in Polar Fog” (Archipelago Books, 337 pages, $24).

Set in a Chukchi community — think Eskimos, though they’re not, quite — in the Russian far north in the years before and during the First World War, “A Dream in Polar Fog” appears on the surface to be a familiar fish-, or more appropriately, seal-or walrus-out-of-water story. John MacLennon, a young Canadian sailor, is grievously injured in an explosion during his ship’s visit to a Chukchi village. The ship having become icebound, three Chukchi men are hired to transport him by dogsled to a hospital in a (relatively) distant Russian town.

Undramatically but decisively, the weather intervenes, and John, minus the better part of both his hands, is stranded. Taken in by the primitive Chukchi, he wills himself to dissolve into their culture, forsaking Western ways and, eventually, Western thought altogether.

Well. The going-native trope can be wearying and hackneyed; often as not it devolves into a simplistic tale in which the outsider from the more technologically advanced culture comes to see the wickedness of his people’s ways through appreciation of the simplicity of life with his adopted tribe: They’re closer to nature (prettier sunsets), more honest (equitable distribution of meager goods), more alive (better sex).

Rytkheu, himself born into a Chukotka village, neither glamorizes the Chukchi’s harsh life nor (overly) demonizes the encroaching whites. True, he touches a lot of the apparently requisite bases: John receives guidance from a wise elder (“Little Big Man”); learns the natives’ language, has adventures and falls in love (“Shogun”); even comes to resemble the natives (“Kim,” with — as always with Kipling — reservations).

But all this, however interesting, seems beside the point, for “A Dream in Polar Fog” — and this is especially dicey for works in translation — thrums in the lower, more visceral range of language itself:

The snow crunched loudly underfoot, and this single sound within the frosty silence spread far around, filling the white space with nasty creaking. It followed the hunter the entire way. And the way was long, through tall ice hummocks, through conglomerations of broken ice. It had been a long time since they had used harness teams in Enmyn: The half-starved dogs had gone wild, having to fend for themselves, and wouldn’t allow themselves to be caught.

Frost bound the polynyas. Not sooner did a melthole appear, than it was drawn over with new, translucent ice.

As John melds with the Chukchi, the narrative becomes almost hallucinatory, even as great events transpire: a tragic accidental killing, a seal hunt, the discovery of a beached whale, feast, famine, an ominous white trader threatening their stability, Bolsheviks rumbling in the distance. One emerges from the novel and its sudden, jarring, most unusual but spot-on ending dazed, dazzled, snow-blind. The book remains in memory as more of state of consciousness experienced than a tale told. A dream in polar fog.

A note on the publisher: Archipelago Books’ specialty is quality works in translation, which they offer in beautifully designed, reasonably priced hardcover editions.

A review of A Dream in Polar Fog from Bookslut

Yuri Rytkheu’s A Dream in Polar Fogis set on the coast of the Chukotka peninsula, a piece of the world rarely visited even by literature. David Masiel gave us the riveting, too-wild-to-be-fiction debut 2182 kHz, about a hard-luck sailor stumbling through the Arctic Ocean and the even chillier waters of personal despair, but it was grounded in the lives of whites, as is most Arctic fiction.

Polar Fog‘s hero is also a white sailor. We meet John MacLennan in 1910, hailing from Ontario, an idealistic, capable college drop-out who’s signed on to sail the Russian Arctic for the adventure of it. He’s not electrifying, but he’s thoughtful, handy and resilient; a heartier embodiment of fair play and human decency would be tough to come by in any climate. The ship he’s sailing on gets icebound along the coast of extreme Northeastern Siberia, John injures himself attempting to free it, and the local Chukcha, native hunters, agree to rush him by dogsled to the nearest hospital in the Russian town of Anadyr.

The rest of the book’s plot is best experienced firsthand, but suffice it to say Rytkheu takes John and the readers deep into the lives of the locals. The Chukcha of A Dream in Polar Fog, hunters who live in huts of reindeer skin, are rendered with character and nuance too rarely afforded indigenous peoples. The narrative follows John, but moves comfortably from his thoughts and opinions to those of the people around him, juggling their individual backgrounds and relative language barriers so masterfully that only when a reader steps back to consider it does the magnitude of the accomplishment sink in.

A Dream in Polar Fog is a tight, pointedly external realist narrative whose larger ideas emerge from the book’s events. Calling Polar Fog an adventure story cheats its richness and history, but it’s too well-written, too exciting and too compelling a novel to be mere ethnography. The muscularity of Rytkheu’s prose and how deftly he paints the natural environment call to mind Jack London’s masterpiece, “To Build a Fire,” a thousand-some miles of distance notwithstanding. Rytkheu immerses his readers in the fantastical landscapes of the Arctic circle, and does so without breaking a sweat. A lesser writer would make more of the physical geography, but Rytkheu doesn’t need to. His elegant, unforced descriptive writing can whip us across leagues of tundra and thread the jagged icebergs studding hyperborean seas, but when the blizzards hit and the characters are trapped in their huts, we’re snowbound there with them under the whale-oil lamp, chewing walrus and hoping for respite.

Of course, Rytkheu didn’t write Polar Fog in English, but in Russian. Previously, his work could be found in English only in obscure tomes from Soviet propaganda publishing houses. Archipelago Books has done English readers yet another service by bringing Rytkheu to the New World in an edition worthy of him, smoothly translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse. Details in the book’s physical presentation contribute to its delectation, from its pleasing near-square shape to the soothing grey of the page numbers and footnotes, which leave a cleaner, more readable page.

In A Dream in Polar Fog, the white man in Chukotka is still a visiting curiosity, but for the reader, for John, and for the more worldly Chukcha there is no ignoring the inevitable collision between tribal tradition and imperial power, nor its inevitable outcome. It may seem an obvious comparison — native writers writing native peoples — but it’s hard not to think of Sherman Alexie’s work mapping the realities of Spokane life after genocide. When John’s friend Il’motch tells a humorous anecdote about being approached by two white men who attempted to trade for supplies with nothing more than soft yellow rocks, John immediately grasps the event’s ramifications: the rocks are gold, and its discovery on the Chukotka peninsula spells certain doom for the Chukcha way of life. As John worries about the future of the Chukcha, so too will the reader. The book ends as Russia’s October Revolution is underway. Communism spared Chukotka a gold rush in the American sense, but the formation of the Soviet Union sparked an enormous influx of non-natives drawn by easy availability of work in the state-run gold mines and associated construction. After the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Chukotka’s industrial economy spiraled, most non-natives fled, and those left behind sank into abject poverty, with the reindeer herds remaining monopolized by state-owned farms. The oil baron Roman Abramovich, Russia’s richest man, became Chukotka’s governor in 2001, and his company Sibneft began exploratory drilling throughout the peninsula. In 2003, Sibneft moved into the Anadyr Bay, where A Dream in Polar Fog is set. Ignoring locals’ protests, they chose a nature preserve as their first site, believing it to hold more than a billion tons of oil. Drilling begins next year.

"Elemental:" a review of A Dream in Polar Fog from Daniel Green in The Reading Experience blog

Yuri Rytkheu’s A Dream in Polar Fog (Archipelago Books) is a very readable novel that also usefully illuminates a corner of the world with which most readers must be entirely unfamiliar. It tells the story of a Canadian sailor who finds himself living with the Chukchi people of northeastern Siberia at about the time of the Russian revolution. Along the way we learn a great deal about the Chukchi way of life and are provided with several adventure-type setpieces that are quite dramatic and entertaining. Rytkheu’s prose has been rendered by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse into a clear and immediate English that no doubt reflects Rytkheu’s own functionally plain style. I would never think of the novel as a classic of Russian literature, but all in all I’m glad I read it.

Thus I find Neil Pollack’s review of the book notably overwrought, probably more indicative of Pollack’s notions about what fiction is for than of the place A Dream in Polar Fog might hold in the canon of world literature. “Yuri Rytkheu’s A Dream in Polar Fog is a reminder of a time when novels had adventure and mystery,” he writes, “before the ubiquity of video made everything on Earth seem familiar, yet also abstract and distant. Its themes are grand, elemental, and simple, comprehensible in the junior high school manner of discussing literature (Man v. Nature, Man v. Himself, and soon), but also tricky and subtle. This is the work of a writer in full command of the novelistic form. It recalls, in both substance and style, the best work of Jack London and Herman Melville, and it is a novel in the grandest sense of the word.”

Pollack doesn’t elaborate on what he means by “tricky and subtle” (or explain how this is compatible with his follow-up statement that Rytkeu “isn’t looking to impress us with his cleverness or with narrative trickery”), other than to repeat in his conclusion that the novel “is both elegant and exciting.” It is not necessarily a disparagment of A Dream in Polar Fog to say that its themes are indeed “comprehensible in the junior high school manner of discussing literature,” or to conclude that subtlety isn’t something a novel like this really needs. Pollack seems to be straining to defend it as also “artistic” at the same time he is elevating “adventure and mystery” to pride of place in our consideration of novels—these are what allow us to call a book like A Dream in Polar Fog “a novel in the grandest sense of the word.” He wants to split the difference between Jack London’s compelling if not particularly subtle tales of adventure and Melville’s more aesthetically intricate metaphysical reveries masquerading as adventure stories.

A Dream in Polar Fog is essentially an ethnographic novel. Whereas the anthropological “information” to be found in London’s fiction is generally secondary to the drama of his adventure plots, in A Dream in Polar Fog relaying this information is really the novel’s primary objective. In keeping with the strictures of socialist realism (under the authority of which this book was originally written and published), the story of John MacLennan’s induction into and embrace of Chukchi society is a vehicle for the portrayal of the Chukchi people as wise and indomitable (although I agree with Pollack that Rythkeu makes an attempt to portray individual Chukchi as motivated by the same human impulses as anyone else) and for providing readers with a detailed portrait of their ways and their way of life. It does succeed in this effort, but I can’t see that this warrants declaring that in so doing it “accomplishes everything a novel should.” It’s defining the form down in the extreme to describe it in terms acceptable even to the Union of Soviet Writers.

Again, I don’t mean to belittle Rytkheu’s book. Among the officially sanctioned fiction published during the Soviet era, A Dream in Polar Fog is probably less compromised than most by its fidelity to the principles upholding the “truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development.” It holds up as a work of literature despite the deformations imposed by the processes controlling its publication—albeit a work of a certain kind, a “simple” story of “simple” people told in a more or less documentary style. By sticking to the descriptive method of fiction-as-ethnography, Rytkheu preserves the integrity of his account of Chukchi culture, and the novel otherwise qualifies as a recognizable piece of adventure fiction. But Neil Pollack seems to think that this particular conception of what novels ought to do is really the definition of the “novelistic form.” Presumably, novels at their best are long on narrative, on ethnographic description, on “elemental” themes.

In my view, what this leaves out is the possibility that novels might aspire to be works of art rather than simply rousing narratives. Pollack almost implies that “a novel in the grandest sense of the word” necessarily avoids any artsy-fartsy “trickery,” even while he praises A Dream in Polar Fog for its elegance and its “maturity” of approach. I don’t know how many readers agree with Neil Pollack that narrative simplicty combined with anthropological detail makes for the “best” kind of novel, but surely such a view at the very least implies that aesthetic values are secondary in our consideration of fiction, that literature is most acceptable when it avoids being too, well, literary.