“Intellect Is Everything”

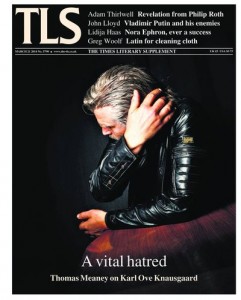

by Thomas Meaney

Karl Ove Knausgaard

BOYHOOD ISLAND

My struggle: 3

496pp. Harvill Secker. £17.99.

Translated by Don Bartlett

978 1 8465 5722 4

There was a time when artists concealed themselves behind their work. The idea of revealing the trifling incidents of their lives may never have occurred to them. It is difficult to imagine Shakespeare or Racine recording their daily trivia for other people’s interest. Perhaps they even wanted to distort the image of who they were. The art of their time was still filled with the exalted poses of heroes and saints. There was an advantage in this: expectations of authenticity exact a toll on today’s novelists, and those who base books on their own lives sometimes seem unconvinced, or embarrassed, by their search for meaning. They take comfort in psychology, which promises to lend their actions intrinsic value. But only rarely do they treat the fragments of their lives as parts of a greater whole and impose a higher coherence.

In the past half-decade in Norway, a writer has recast the confessional novel in hyperbolic form. Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume, 3,600-page My Struggle is a mercilessly quotidian epic of the author’s journey from boyhood to fatherhood. It is not so much original as extremely, almost fanatically, untimely. Knausgaard’s narrator openly longs for the opposite shore of the Enlightenment, when social life, he likes to think, was saturated with purpose and meaning. But he also believes there is no going back; that he must make his home in a disenchanted world. He often rails against the evaluations of psychology, but while doing so gives us a sharp sense of his inward irradiations. His solution is not to ignore or transcend or even aestheticize the indignities of day-to-day living – the pram-pushing, the nappy-changing, the school run – but to linger for a while over every difficult inch.

The opening volume of My Struggle – A Death in the Family – opens with an account of the death of a heart. “For the heart, life is simple”, Knausgaard writes, “it beats for as long as it can.” The author goes on to describe the entry of bacteria into the bloodstream, which seem to abide by a kind of “gentleman’s agreement” with the dying body. When they arrive at the heart, the bacteria find it “strangely desolate”, like “a production plant that workers have been forced to flee in haste, or so it appears, the stationary vehicles shining yellow against the darkness of the forest, the huts deserted, a line of fully loaded cable-buckets stretching up the hillside”. This is very fine writing – how close that “shining yellow” comes to turning the simile rogue with its excessive naturalism – but Knausgaard only keeps it up for a few pages, as if to sharpen the contrast with what follows. His overture signals that he knows “good writing”, that he can perform it, but that his novel will be about things that virtuosic writing cannot get at. Within a few pages, like the bacteria entering the corpse, Knausgaard starts to invite clichés into his work: things start flowing through his hands “like sand” and “falling like the drop of a hat”. What is mysterious is how the gamble pays off: the flattening of the prose only seems to contribute to its magnetism.

Knausgaard’s style in My Struggle marks a break with the flourish-prone prose of his previous novel, A Time to Every Purpose under Heaven (reviewed in the TLS, February 6, 2009), which, among other things, treated the book of Genesis as a mere reduction of a more psychologically complicated and morally ambivalent epic set in Norway. In an interview with the Paris Review last December, the author partly credited his scaling down of tone with his revelation at reading the Swedish playwright Lars Norén, whose 1,680-page diary caused a scandal in the Stockholm theatre world when it was published in 2008. En dramatikers dagbok, which Norén retrospectively called a novel, heaped venom on Norén’s fellow directors and actors, and recounted his life in unsparing detail. Here is a typical entry:

“I was sitting watching a worthless Harrison Ford movie when I suddenly got a bad bout of stomach cramp. Went to the lavatory. Shit on my shorts. Mainly blood. A significant amount. I cleaned up, washed my clothes, hung them up to dry, packed my rucksack, shoved in cigarettes, glasses, book, money. Phoned the emergency room at Danderyds Hospital, but the nurse who answered said she didn’t think I needed to come in. She said the blood might be the result of an inflammation which I’ve got because I frequently need to go to the lavatory. She told me to wait and see. Fell asleep late. Restless. Woke at 7 this morning. Beautiful outside. Calm, minus 14 degrees celsius. Sun. Went shopping at Rimi. Sat and read between cramps. Called Charly and said that unfortunately I couldn’t make it. Went out to buy cigarettes. Slept two hours. Spoke for a while with Masja and Linda. Slept again. I love the current silence. Don’t know if I can travel to Gotland. Will have to see if there is more blood tonight.”

It says something about Knausgaard that he read a grim passage like this and saw possibilities for his art. In My Struggle, the accounting is more solemn, almost Lutheran in its austerity – Knausgaard has opted for an unusually formal variant of Norwegian for this book – but a touch of Norén’s plodding insistence remains:

“Today is the twenty-seventh of February. The time is 11:43 p.m. I, Karl Ove Knausgaard, was born in December 1968, and at the time of writing I am thirty-nine years old. I have three children – Vanja, Heidi, and John – and am in my second marriage, to Linda Bostrom Knausgaard. All four are asleep in the rooms around me, in an apartment in Malmö where we have lived for a year and a half.”

From the outset, we have the uncanny sense that Knausgaard is not writing about himself so much as for himself. The facts laid out by the narrator match the facts of the author’s own life. Whatever else My Struggle is about, Knausgaard makes us feel he has staked his life on it. He is committed to capturing the tedious, repetitive, microscopic mood switches of human consciousness – and the result is paradoxically absorbing.

The formula Knausgaard has devised for the project is simple: “Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance”, he writes in A Death in the Family. My Struggle shifts variously between Knausgaard writing his novel in the present, reflections on his early career as a writer and student, and the time of his childhood in 1970s Norway. Knausgaard was born, just one year before the major discovery of oil in the North Sea promised to make the country’s social democratic dreams something close to a reality. On the island of Tromøy in southern Norway, we observe Knausgaard’s mother committing herself to leftist causes, while his father serves on the town council and teaches at the local elementary school. But at home this “new” Norwegian man is a tyrant, who drills fear into his youngest son and snuffs out his joys one by one. The young Knausgaard comes to nurse a vital hatred for him:

“I hated dad, but I was in his hands, I couldn’t escape his power. It was impossible to exact my revenge on him. Except in the much-acclaimed mind and imagination, there I was able to crush him. Could grow there, outgrow him, place my hands on his cheeks and squeeze until his lips formed the stupid pout he made to imitate me, because of my protruding teeth. There, I could punch him on the nose so hard that it broke and blood streamed from it. Or, even better, so that the bone was forced back into his brain and he died.”

Much of My Struggle is the struggle of Karl Ove against his father. At times this hints at a deep conflict of world views, such as when Karl Ove swears he has witnessed a face in the water of a shipwreck reported on the evening news, which his father takes as a sign of his weak son’s worrisome attachment to Christianity. But for the most part the father’s terrorism is domestic: he forces his son to eat four apples in a row, yells at him for losing his socks, grounds him for breaking the television. The transgressions are banal; the responses are genuinely menacing. As Knausgaard gains more perspective on his father, who dies of alcoholism at the end of A Death in the Family, the struggle becomes to not end up like him, or be dominated by his memory. Karl Ove feels his father’s presence in his own attitude towards alcohol, Christianity, Norwegian social democracy. But he is determined not to repeat the sins of his father on his own children. In the third volume, Boyhood Island, which has now been translated into English, he reports some success:

“When I enter a room, they don’t cringe, they don’t look down at the floor, they don’t dart off as soon as they glimpse an opportunity, no, if they look at me, it is not a look of indifference, and if there is anyone I am happy to be forgotten by it’s them. If there is anyone I am happy to be taken for granted by, it is them. And should they have completely forgotten I was there when they turn forty themselves, I will thank them and take a bow and accept the bouquet.”

But My Struggle contains another struggle as well, the struggle to become an artist, and this is the more complicated one. There is a startling confession that sets Knausgaard’s mind running in Volume One: “When I look at a beautiful painting I have tears in my eyes but not when I look at my children. That does not mean I do not love them, because I do, with all my heart, it simply means that the meaning they produce is not sufficient to fulfill a whole life. Not mine at any rate”. My Struggle is also a struggle to fulfil this need for meaning, which Knausgaard quenches in moments of the sublime, which arrive sporadically amid the overwhelming mundanity of the book. Here, in A Death in the Family, is Knausgaardon the train from Stockholm to Gnesta:

“I wasn’t thinking of anything in particular, just staring at the burning red ball in the sky and the pleasure that suffused me was so sharp and came with such intensity that it was indistinguishable from pain. What I experienced seemed to me to be of enormous significance. Enormous significance. When the moment had passed the feeling of significance did not diminish, but all of a sudden it became hard to place: exactly what was significant? And why? A train, an industrial area, sun, mist?”

There is something extremely humanistic and Romantic about this passage. Knausgaard seems to be able to conjure up his experience of beauty all on his own – with only minimal support from nature. He goes on to say the light he sees from the train reminds him of his favourite painters: “Vermeer evoked the same, a few of Claude’s paintings, some of Ruisdael’s . . . some of J. C. Dahl’s, almost all of Hertervig’s . . . . But none of Rubens’s painting, none of Manet’s, none of the English or French eighteenth-century painting with the exception of Chardin, not Whistler, nor Michelangelo, and only one by Leonardo da Vinci”. The type of devotion exhibited here – “only one by Leonardo” – is arrestingly, amusingly precise; but what links these painters who stir him? Knausgaard cannot say for certain; he hazards it has to do with a “certain objectivity, by which I mean a distance between reality and the portrayal of reality, and it was doubtless in this interlying space where it ‘happened,’ where it appeared, whatever it was I saw, when the world seemed to step forward from the world”. After this clawing towards the sublime, the author unleashes a cascade of thought about contemporary art:

“The situation we have arrived at now whereby the props of art no longer have any significance, all the emphasis is placed on what the art expresses, in other words, not what it is but what it thinks, what ideas it accrues, such that the last demands of objectivity, the final remnants of something outside the human world have been abandoned. Art has come to be an unmade bed, a couple of photocopiers in a room, a motorbike in the attic. And art has come to be a spectator of itself, the way it reacts, what newspapers write about it; the artist is a performer . . . . Those in this situation who call for more intellectual depth, more spiritual depth, have understood nothing, for the problem is that the intellect has taken over everything. Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t bodies anymore, but ideas of bodies, something that is situated in our own heaven of images and conceptions within us and above us, where an increasing large part of our lives is lived. The limits of that which cannot speak to us – the unfathomable – no longer exist. We understand everything, and we do so because we have turned everything into ourselves.”

“Everything has become intellect” – it could be Hegel we’re reading. And this diatribe comes close to the view Hegel put forward in his own lectures on aesthetics, in 1828: once upon a time, Hegel argued, art was about saints and heroes. After the Reformation, artists became interested in the fact that most people are not saints and that lives are determined by externally imposed constraints. It is here, under the regime of the market, that, Hegel says, “everything that is called the prose of life belongs”. It is impossible to invest subjects in such an age with the complete harmony of content and form required for beauty because of the finite nature of everyday life. But if the moderns cannot rival the ancients in terms of beauty, Hegel still thought they had “liveliness” and “absorption” on their side. The Dutch masters might no longer be able to paint beatific Madonnas, but they could paint a woman knitting socks or receiving a letter, provided they concentrated sufficient power on heightening her vitality. They could, as it were, force meaning into her features with the sheer virtuosity of their brush.

Knausgaard’s project is similar but also crucially different from the Dutch masters who were among the first to make a home in the disenchanted world. He wants to push his way towards the sublime moments of our earthly existence, but he believes it can be done without virtuosity:

“I sat leafing through a Constable book for almost an hour. I kept flicking back to the picture of the greenish clouds, every time it called for the same emotions in me. It was as if two different forms of reflection rose and fell in my consciousness, one with its thoughts and reasoning, the other with its feeling and impression, which even though they were juxtaposed, expulsed each other’s insights. It was a fantastic picture, it filled me with all the feeling that fantastic pictures do, but when I had to explain why, what constitute the “fantastic,” was at a loss to do so . . . . But the moment I focused my gaze on the painting again all my reasoning vanished in the surge of energy and beauty that arose in me. Yes, yes, yes, I heard. That’s where it is. That’s where I have to go.”

Knausgaard finds the sublime in the everyday; he also finds it in classic pieces of art. He shows us that these realms, as well as the realm of love, cannot be fully intellectualized.But unlike Joyce or Woolf, who required a renovation of language to communicate this, Knausgaard prefers to show his narrator bumping up against his own limits of expression. This may be less satisfying to read on the level of the sentence, but it captures something about our reality, and our relationship with art, which seldom moves us in the ways we expect, and whose effects are no less strong for the clichés we use to describe them, just as our passions are no less genuine for our use of borrowed language. “You cannot chase the Holy Grail with a pram”, said Karen Blixen. But Knausgaard shows that, with enough intensity, you can.

In A Time to Every Purpose under Heaven, Knausgaard dramatized the story of art as described by Hegel, and he took it a step further, by telling the story of angels in Western art: at first the angels were depicted as the rare, austere messengers from God; then they gradually became the pudgy, decadent cherubim of Caravaggio; then they were nearly exiled from our consciousness altogether. In Knausgaard’s telling they became seagulls on the Norwegian coast, where only a few residents dimly remember their former glory. Knausgaard’s project here was to bring the Old Testament back down to earth and treat its parables as pitiless reductions of his much richer tapestry. But in My Struggle, the aim is the reverse: to lay out his whole profane existence for sacred inspection. When the writing is at its most mundane we feel faint biblical echoes in the background.

Simply on the basis of My Struggle’s length, it seems, critics have compared Knausgaard with Proust. There are some similarities between the two: both tell stories of artistic education and taste formation: just as Proust goes through the apprenticeships of Bergotte, Elstir and Berma, so Knausgaard worships at the altars of Queen, The Clash and the poet Olav Hauge. (Unlike nearly every contemporary American novelist, Knausgaard makes his movements between so-called high and low culture appear seamless and natural, not so much a joy ride between registers, strenuously exhibited, as a matter-of-fact reflection of his tastes). But the major difference with Proust is in the way My Struggle is engineered to operate with the reader: Proust carefully curates his moments of revelation; Knausgaard leaves it to the reader to distinguish between the meaningful and meaningless.

Boyhood Island revisits much of the same territory as the previous two volumes but in a much more sustained fashion. Here Knausgaard looks back on his difficult childhood while only very rarely returning to the perspective of the writer and father he has now become. This volume contains the longest stretch of total recall that Knausgaard has yet allowed himself in the course of the work. It opens with the narrator claiming that he can’t remember anything of “this ghetto-like state of incompleteness that is what I call my childhood”. He wishes we could assign different Christian names to ourselves during our different stages in life – to the foetus, the child, the teenager, the young adult, the man, the old man. The idea that all these selves are presumed to form some kind of coherent being is absurd to the author. But then comes the plunge where, after saying he remembers nothing of his childhood, he suddenly remembers everything – how to speak like a child, think like a child, reason like a child

Boyhood Island reverberates with the joys and anxieties of early youth, and Knausgaard brilliantly recreates their exaggerated feel. Here he is on his boyish fixation with construction workers: “What fascinated us most apart from the change in the landscape they wrought were the manifestations of their private lives that came with them. When they produced a comb from their orange overalls or baggy, almost shapeless, blue trousers and combed their hair”. He communicates everything from the loud sound a toothbrush makes in his head to the minute discoveries of childhood that have the force of major revelations: “I came to the conclusion that cornflakes were best when they were crispy, before the milk had soaked into them”. There are powerfully felt scenes of sexual and intellectual awakening, and if the book has its longeurs it’s mostly because we’ve grown accustomed to Knausgaard switching between time sequences, or following an episode about shopping for groceries with an exegesis on the fate of angels.

It is too early for English readers to tell what the relation of this half of the book will be to the whole. We do now know that they can continue to rely on the deft and sure translations of Don Bartlett, who has recently signed a contract to translate the entire work. And whatever the outcome, there is already the sense that the author’s views going in will not be the same as the ones he comes out with. Knausgaard looks with envy on Rimbaud, whose final act as an artist was to quit art altogether, and we sense that he too is looking for an exit. We already know the final line in the final volume to be: “And I’m so happy that I’m no longer an author”. It would be a mistake to read My Struggle as a struggle away from art. But its extreme artlessness creates a far more intense realism than we might have thought possible – a confessional novel that outdoes most confessions – and that makes us feel that these are things as they really are for a forty-year-old man from Norway.

Dear Mr. Meaney,

Thank you for a meaningful and insightful portrayal of Knausgaard’s work. I am halfway through Book 2 and am absolutely consumed by him. You did a terrific job of gently extracting details to reveal his brillance and introspection. I appreciate your summary and closer review of Book 3, which I already own. Like me, I can tell you look forward to the arrival of Book 4 and beyond. Thank you again.

Best regards,

JC Lowe

Washington DC

Thanks for your review. I haven’t had the chance to read this author yet, but I’m curious about him. Specifically, why almost everyone sings fanfares to this author, mostly finding rejoice in the fact that he writes beautifully about everything in life? In your review too, I haven’t noticed any exploration of his weakness. Is this what a real critical analysis, which is supposed to be at least somewhat objective and analytical? It’s all just fanfares, so far. For me, this lack of critical analysis creates the most obvious kind of skepticism. I haven’t found an answer in your review, or in others, why should one (who studies and works a lot, not relying on welfare, state or private) read this huge series of books? From reading about this book it seems that it belongs in a non-fiction category. What’s literary about it? Is there any imaginative in it? Yes, perhaps, it is a beautiful and intelligent, but overtly long and, perhaps, derivative project? I mean, why should one occupy him/herself with reading thousands of pages how some Scandinavian dude lives in a state of permanent anxiety & boredom. It seems that the subjects of this projects are primarily anxiety & boredom. An emptiness of one’s life, that he tried to solve via marriages, having three kids, and then writing a bunch of weeping diaries, believing that the world would be interested to know them. From the literary & pragmatic point of view, what’s the point of reading some guy’s struggle in a socialist country with emasculating welfare, when there are so many other interesting books to read, and real work to be done in life? I mean, the canon of Western literature is so huge and varied. Take Plato, Aristotle, W. Shakespeare, Dante, M. Cervantes or L. Tolstoy, for example. Most of the people I know who live their lives in the pursuit of knowledge & meaning work their asses of (regardless of fields – athletic, teaching, banking, medical, engineering, etc.) and because of that find some meaning. Also, the engagement with surrounding community helps. This book project seems like another derivative bullshit piece of work becoming a cult by some art critics & artists (like with D.F.W., whose suicide immediately made him a certain cultic figure) just because it’s long and about boredom. Doesn’t one has anything else to do, beside reading thousands of pages about the utmost banality of life? There are so many other things in the world where real attention and action is needed. From primitive like building a road to something like doing research on things that matter (natural sciences, medical research, liberal arts), not pretend. Thanks for your time & attention.

Instead of speculating about the effect of the books, go ahead and read them. Then come back with comments.