Praise

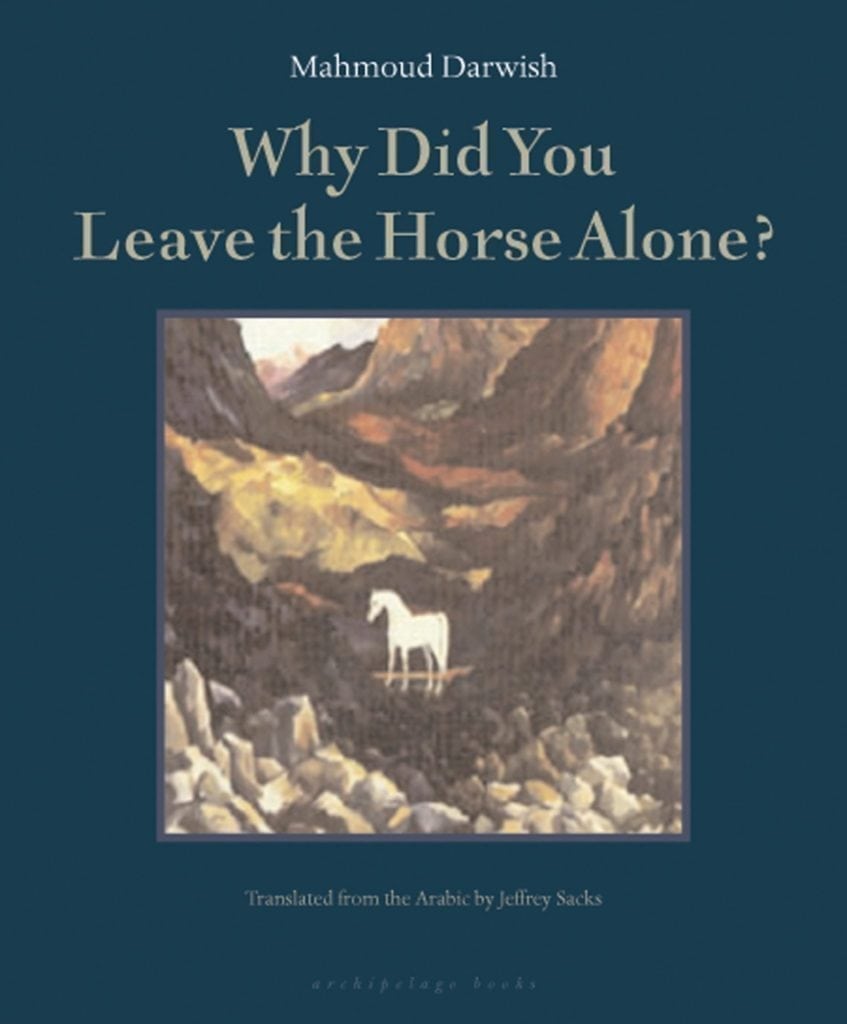

The journey continues and the conversation will carry on, in the attempt to look for Mahmoud Darwish among the words.

Voice Over is a short but affecting sequence, with a slightly experimental feel to it, its author trying to come to grips with the death of his friend and colleague through a variety of approaches. A beautiful little pocket-sized pamphlet-volume, it is well-worthwhile.

Breytenbach's passionate desire to know and serve the truth, whatever it may be and whomever it might offend, is deeply admirable.

In these sentences we hear the voice of the old activist, in love with life and human potential.

Definitely a writer worth looking into, this creative powerhouse will give you some real literature to sink your teeth into.

Whereas Mouroir makes the most of ambiguity and shapelessness, Voice Over shows Breytenbach to be equally talented when working in a more directed and formal space.

While a number of translators have carried Darwish's poems into respectably clear English, none have, like Breytenbach, transported the very essence, the gentleness of the tone, the luscious but spare vocabulary, grounded in everyday objects: bread, coffee cups, olive trees, bird coops.

Extras

From the author:

Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian poet (1941 – 9 August 2008), was a friend. I was on Gorée Island when I learned of his death during the course of an open-heart intervention in Houston, America. We had been together a few weeks earlier in Arles, the south of France. Even at noon the foyer of the hotel where we stayed was as if drained of light by dusk. He knew how serious his condition was — it was either the very risky operation or the possibility of dying at any moment from an exploding aorta — and with an ironic smile he speculated about his chances of survival. That night, as the sun was setting in a yellow flood over the ancient open air Roman theater and as birds began singing the accumulated sweetness of a summer’s day, he publicly read one last time from his work. The poems were shot through by an ongoing conversation with death. Immediately after his passing, I started writing the above series as fragments of a continuing dialogue. In West Africa it was then the onset of the rainy season moving north, the ‘petit hivernage,’ when black-blue clouds would skitter and close the skies.

It was also the beginning of a new moon’s waxing to fullness. Over the following weeks I was to travel north — first to Catalonia and then on to Friesland where Tsjêbbe Hettinga, the blind word magician, had invited me to participate in a literary festival. The poems reflect this trajectory. Along the way it was refreshing to be bathing in Mahmoud’s verses.

Translation — that is, to proceed from one language to the other — is also a journey. Landscapes change, winds with the smells of unfamiliar growth come down from the highlands like news to the valleys, your shadow will get out of shape, and the song remains as a go-between tongue from the known to the unknown. George Steiner once said that translating is an intense, profound and provocative activity, at times intimate and upsetting, because of the extreme danger that you may lay a hand on the essential being of the other. I consider these fragments as ways of paying homage. Perhaps too, an attempt to draw the veil from the known face which has now gone silent.

MD had always been a prolific poet. One could interact with him forever. The present ‘collage’ touches upon transformed ‘variations’ of his work, at times plucked from different poems and then again by way of approaching a specific verse, with my own voice woven into the process. The images, and to an extent even the rhythms and the shaping, are his. I don’t know Arabic and have to make do with English and French approximations. I did have the luck of hearing him read in his tongue on several occasions and the sounds and movement of that ancient vehicle always struck me. I had to step a language away in order to get closer to him in English; these versions thus grew retroactively from Afrikaans efforts, with the intention also of facilitating a conversation between the two languages. The result cannot be properly described as a true ‘translation.’ At times an echo or an association presented by the English possibilities opened a new way back into the Afrikaans.

The journey continues and the conversation will carry on, in the attempt to look for Mahmoud Darwish among the words.

Breyten Breytenbach

New York, December 2008