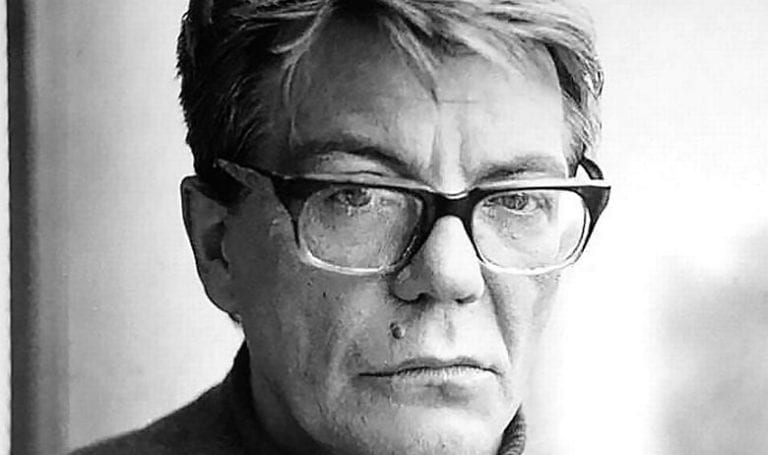

“Lojze Kovačič, the Greatest Undiscovered Cosmopolitan Writer of the South Slavs”

– Miljenko Jergović

First published in Croatian in Jutarnji list (Zagreb), February 9, 2019

Translated from Croatian by Michael Biggins (draft 27 Feb 2019)

Sometimes, even in a completely illiterate society such as Croatia has lately become, it happens that certain writers and their works rise up to the level of icons of their day, the gold standard for style, thought and creativity in both life and text. As a rule these are very local, yet cosmopolitan writers whose cosmopolitanism derives from their ability to make the distinctively Chilean, Mexican, Austrian or Norwegian aspects of their worlds not just universally comprehensible, but easily translatable into any other local distinctiveness. There is at least one contemporary writer still unknown south of the Sutla River who is cosmopolitan in his local distinctiveness and great in the way that Thomas Bernhard, Roberto Bolaño and Karl Ove Knausgaard are great. Who, moreover, produced the preponderance and most important part of his work by dealing with himself and the circumstances of his life and environs. He didn’t write pure autobiography, and at the time he was writing the concept of auto-fiction didn’t even exist. Lojze Kovačič wrote about himself as his primary subject the way Joyce wrote about Dublin, and he did it at a time when that kind of writing not only wasn’t in fashion, but was viewed by many as substandard and shameful.

Who was Kovačič and what provided the frame for his subject? He was born in 1928 in Basel as the youngest child of an émigré of modest means who in 1899 had set out from his homeland into the wider world in search of his fortune. In the course of his wanderings he learned the furrier’s trade and married Lojze’s mother, herself the child of a mixed Franco-German marriage who identified culturally and linguistically as Swiss German. The Kovačič family didn’t particularly prosper even in Basel; they lived quite modestly, and throughout this time the elder Kovačič, dissatisfied with his host country and acutely aware of his subaltern status as a migrant, harbored some vague notion of returning to Slovenia. Consequently, he never adopted Swiss citizenship, even though it was available. Then suddenly, on the eve of World War II the Swiss authorities, in an effort to unburden the country of any and all undesirable ethnic and immigrant ballast, proceeded to expel all aliens who had failed to take Swiss citizenship. Thus the Kovačičes arrived in Slovenia as near paupers, classic refugees, initially settling outside Novo Mesto. It was here that, after an idyllic German childhood in Basel, Lojze not only encountered the Slovene language for the very first time, but also a new, unprecedentedly foreign reality. This alone would have been enough for one lifetime and the literature it produced. But this was just the beginning. In many respects the elder Kovačič was a typical member of the Central

European underclass, a disaffected Catholic and a reflexive anti-Semite. He was a supporter of Hitler, because Hitler was going to unify Europe and get rid of the Jews, sentiments that of course Kovačič, Sr. didn’t bother to conceal during the occupation. He died in 1944. One year later, just as predictably, the victorious communist Partisans arrested his German widow as a presumed Nazi collaborator, along with his grown daughter, Lojze’s sister, and her little girl, and deported the three of them across the border to Austria, where they wound up in a displaced persons camp.

At that time, in 1945, the seventeen-year-old Lojze Kovačič was sentenced to three months in prison. When he was released, he had nothing – not a home, or a family, or the freedom to cross the border and join his mother, sister and niece. He lived as an outcast, selling torn-up scraps of old newspapers outside public toilets as pauper’s tissue. He was already acutely aware that he was going to spend the rest of his life as the enemy, or at the very least as the enemy’s offspring. Even though he did not actively oppose the regime or write on political topics, he endured endless harassment at the hands of the police, the courts and the country’s cultural apparatchiks, and he remained suspect in the extreme as a writer and cultural figure. For most of his life he supported himself as a puppeteer, a teacher of puppetry to children, and as the director of a Ljubljana puppet theater. For several years he produced the puppetry program for the summer Children’s Festival in Šibenik on Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast. He lived out his life just as the events of 1938 and 1945 had promised he would – as a complete and irredeemable outsider. But because Slovene culture was always far more dynamic than Slovene society – something you could never say about Croatian culture – Lojze Kovačič achieved recognition remarkably early. In 1969 he was awarded the Prešeren Foundation Prize, and in 1973 he received the Prešeren Prize itself, Slovenia’s most prestigious award for contributions to culture. Twice he was distinguished with Župančič Awards. Even though he was socially ostracized and politically suspect, Slovene culture made good on its debt to him. He was inducted into the Slovene Academy. He met Slovenia’s independence from Yugoslavia in 1991 with a high degree of restraint, neither jumping on the democracy bandwagon nor fanning anticommunist flames; in other words, he did nothing that he hadn’t already been doing and writing about under communist Yugoslavia. He died in 2004.

Lojze Kovačič is probably the most important Yugoslav writer you’ve never heard about. And probably one of a handful of the most important Yugoslav prose writers and novelists, period. Until recently, just one of his books had been translated into Serbian (Reality, published by Narodna knjiga in 1973), and one other into Croatian (Three Women released by Cankar Publishing in 1985). Then suddenly, practically out of nowhere, and probably thanks to the initiative and passion of the translator Božidar Brezinščak-Bagola, two major Kovačič novels in Croatian translation were published at once, beginning with the 2017 appearance from Alfa of the first two volumes of Newcomers (about which I had previously heard nothing, even though I keep very informed about developments on our literary scene), followed by Crystalline Time, published by Meander in 2018.

Newcomers is Kovačič’s best known novel, which in a recent survey of Slovene critics and literary historians was voted the best Slovene novel of the 20th century. I first read this enormous, multi-volume novel some twenty-five years ago. In the years that followed I reread it, both haphazardly and in its entirety. The book often figured in my thoughts, whether in connection with my life or my writing. (And all that time it seemed incredible to me that the book hadn’t been translated into Croatian or Serbian.)

Crystalline Time deals with the same themes and segments of time as Newcomers, and occasionally even with the same events, albeit in highly compressed, fragmentary form. Of course, the two books originated at different times, and thus the author’s emotional and intellectual perspective on those events and on himself is also quite different. Kovačič, like Bernhard, does not disdain to repeat himself, nor is he overly concerned about surface similarities between his various texts. He writes for himself, as though his ulterior motive is to transform himself into text, to disembody himself and all that is, so that it can be recreated as text, as the novel. And if at first he doesn’t succeed, he’ll try again. And on and on, for as long as he lives.

Crystalline Time begins on July 23, 1988 and ends in a single sentence on June 14, 1990. That sentence is classic Kovačič and reads, “Ripeness is All.” In just under two years the Slovenes had experienced an internal deluge of national consciousness. At the beginning, as the author observes, is the infamous court martial in Ljubljana, at which Janez Janša and three of his colleagues were convicted of conspiracy against the Socialist Federated Republic of Yugoslavia and sentenced to prison. But this is merely an outward biotope of the inner world, a moment from the unknown present which for Kovačič serves as a framework for recalling a past that remains present. Not only does the present moment not cause him joy, it frightens him, ”Fanatical love for one’s homeland, for justice, becomes a veritable pulse of energy for society, but for the individual it harbors double the risk, to the extent it’s transformed into a passion that leads him down a single path. It deforms him, it destroys his heart and his sensitivity to life. It leads him straight down the path to hell. You must never bow to anyone, including the collective violence of your own people.”

Lojze Kovačič was a Christian, a Catholic, who experienced spiritual and theological matters deeply, intensely and most unconventionally. (I suspect this is what has drawn Brezinščak-Bagola to him.) Apart from the fact of being surrounded by a communist, atheistic society, Kovačič’s God is distinguished by his solitude. Nowhere is there a trace here of any community of the faithful, just as there is a complete absence of ecclesiastical fetishes and totems. “When in the course of my wanderings I’ve come into direct contact with the Church, I’ve never had the feeling that God was any more present within its walls or around them than anywhere else…. Of all the architecture in existence, the church has uglified the earth and put a chill in the sky most of all.” For Lojze Kovačič the human conscience is the supreme proof of God’s existence.

It is extraordinarily interesting and deeply moving to read of his long search for God in Crystalline Time, this prose essay cum theological reckoning of an individual with himself and with the world of animate and inanimate things around him.

He despises the architect Jože Plečnik and in so doing comes close to offending the reader, most of all because there’s no objecting to Kovačič’s disdain. He is an eccentric, a sex addict, an unfaithful husband, and someone who with a clear conscience can write a sentence like this, “Kind creatures distinguish themselves in nothing so much as their ability to listen to others.” Kovačič writes in good Slovene, in sentences and paragraphs and whole works that he fits into his own, private syntax, punctuated with an abundance of ellipses that hint at the rhythms of thought.

Lojze Kovačič is one of the most important writers of our time, one who confirms our world in both text and deed.

Original Croatian text: https://www.jutarnji.hr/komentari/lojze-kovacic-najveci-neotkriveni-svjetski-pisac-u-juznih- slavena/8359178/