David Shulman has written a thoughtful and engrossing paean to Karthika Naïr’s Until the Lions in the September 24th issue of the New York Review of Books. Shulman’s piece situates Naïr’s work in the long and intricate history of the Mahabharata, praising Until the Lions for its nimble play of poetic forms and deep emotional register, as well as Naïr’s inventive reconstruction of the Mahabharata’s less-sung stories. You can find the review here, and read an excerpt below:

David Shulman has written a thoughtful and engrossing paean to Karthika Naïr’s Until the Lions in the September 24th issue of the New York Review of Books. Shulman’s piece situates Naïr’s work in the long and intricate history of the Mahabharata, praising Until the Lions for its nimble play of poetic forms and deep emotional register, as well as Naïr’s inventive reconstruction of the Mahabharata’s less-sung stories. You can find the review here, and read an excerpt below:

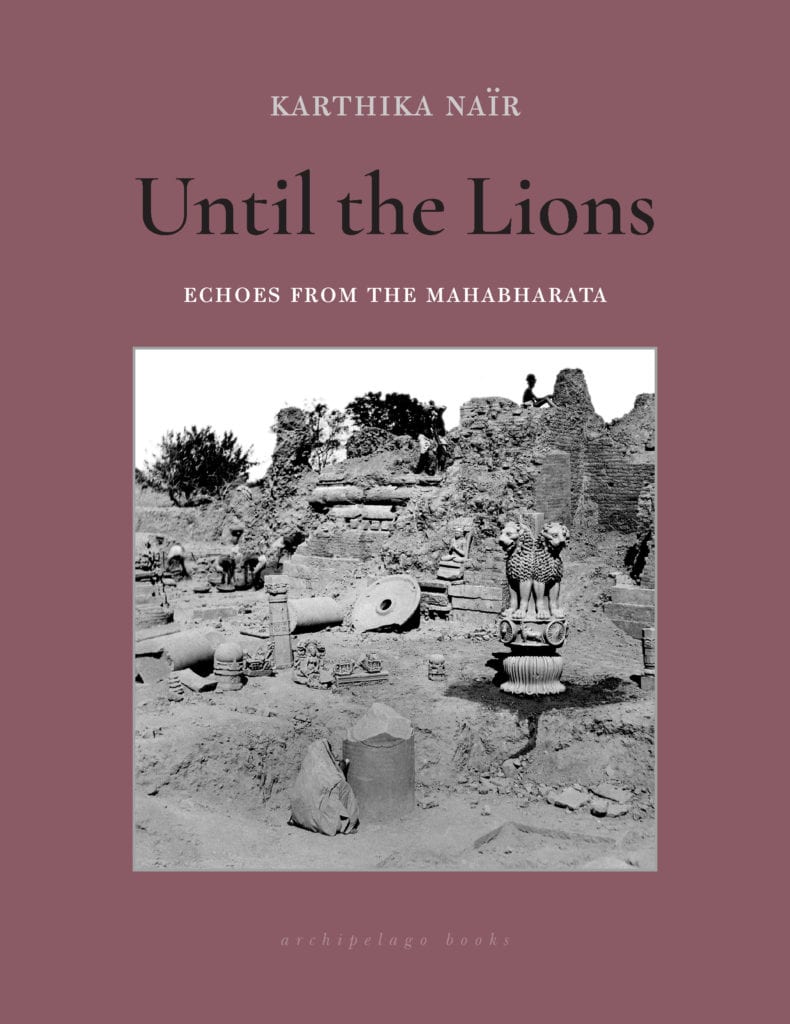

The most lyrical of all such attempts to see the Mahabharata through the eyes of its characters is the remarkable dramatic poem Until the Lions by the Kerala-born, Paris-based poet, dance producer, and librettist Karthika Naïr. She has given her book an appropriate subtitle: “Echoes from the Mahabharata.” The thirty haunting, heartrending chapters, in a wide range of forms and styles, resonate powerfully with one another…

Nearly all the chapters are first-person dramatic monologues uttered by female characters known from the Mahabharata (with the exception of one newly invented voice, that of the clairvoyant canine Shunaka, who reembodies the speaking dog Sarama mentioned at the very beginning, or one of the beginnings, of the epic). The female voices are, almost without exception, tormented, ravaged, grief-stricken, bitterly lamenting the irrevocable, unthinkable losses that their fathers, husbands, brothers, brothers-in-law, lovers, and sons have inflicted on them. I don’t think I have ever seen a description of rape as unflinching as Sauvali’s rage at King Dhritarashtra and the configuration of sycophantic politicians and courtiers who force her to submit to him. Sauvali exemplifies a prominent pattern in these chapters: women whose names are known from the Sanskrit epic but whose character and inner experience are muted there suddenly come to life as full-blooded people caught up in the destruction endemic to a male world (well, maybe to any human world)…

Karthika, in the voice of Uttaraa, has articulated something I remember all too well from my own wartime service in Lebanon. Among the soldiers in my unit, only one, I think—our gung-ho commanding officer—identified with the specious rhetoric coming at us from the politicians back home in Jerusalem. Karthika’s Mahabharata is, among other things, a passionate antiwar manifesto; she and her characters are sensitive to the perversion of language that is always needed to generate more dead heroes, and to the cost borne by those who survive…

This is a Mahabharata for our generation. It includes stories that have attached themselves to the classical epic via local, regional traditions…Her poems share the kaleidoscopic quality of the epic text, its persistent, dizzying perspectivism as it moves from one episode to the next, one ardent speaker to another.

One could also see the Mahabharata, as the anthropologist Don Handelman has suggested, as a vast laboratory for existential experiment, in which the great themes and above all the ethical quandaries of a civilization can be brought to light, played out, and examined. Such themes are not abstract entities but lived human realities, mostly agonizing and opaque, eluding any simple or, indeed, possible resolution. From a point somewhere deep within this laboratory, Karthika Naïr has captured in words the tonality of this mammoth text.